“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” — The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, July 4, 1776.

This coming Thursday will mark the 237th anniversary of the signing of our Declaration of Independence from Great Britain.

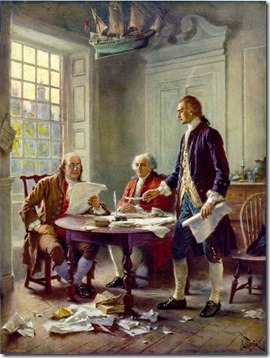

When armed conflict between bands of American colonists and British soldiers began in April 1775, the Americans were ostensibly fighting only for their rights as subjects of the British crown. By the following summer, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, the movement for independence from Britain had grown, and delegates of the Continental Congress were faced with a vote on the issue. In mid-June 1776, a five-man committee including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin was tasked with drafting a formal statement of the colonies' intentions. The Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence — written largely by Jefferson — in Philadelphia on July 4, a date now celebrated as the birth of American independence.

Even after the initial battles in the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did — like John Adams — were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in October 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of his words reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conservatives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published "Common Sense," in which he argued that independence was a "natural right" and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its first few weeks in publication.

In March 1776, North Carolina's revolutionary convention became the first to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion

Jefferson had earned a reputation as an eloquent voice for the patriotic cause after his 1774 publication of "A Summary View of the Rights of British America," and he was given the task of producing a draft of what would become the Declaration of Independence. As he wrote in 1823, the other members of the committee:

"unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections. I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress."

As Jefferson drafted it, the Declaration of Independence was divided into five sections, including an introduction, a preamble, a body (divided into two sections) and a conclusion. In general terms, the introduction effectively stated that seeking independence from Britain had become "necessary" for the colonies. While the body of the document outlined a list of grievances against the British crown, the preamble includes its most famous passage:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

The Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, and the following day 12 of

As the first formal statement by a nation's people asserting their right to choose their own government, the Declaration of Independence became a significant landmark in the history of democracy. In addition to its importance in the fate of the fledgling American nation, it also exerted a tremendous influence outside the United States, most memorably in France during the French Revolution. Together with the Northwest Ordinance, the Constitution (including the Bill of Rights), the Declaration of Independence can be counted as one of the three essential founding documents and the organic laws of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln was dedicated so much the Declaration that he called it “an apple of gold set in the silver frame of the Constitution.” He believed that the Declaration embodied all of the basic principles of the United States and that the Constitution was designed to codify those principles as a part of our organic law.

Today not many people have read the Declaration. I would venture that less than 30% of our high school or college graduates have ever read the entire document. My estimate is not based on any scientific evidence, but it is based on empirical data obtained from personal observation. Unless a student is enrolled in a very good college prep school or studying law or political science in college I doubt very much that they have had any exposure to the entire document. This includes most of the talking heads on TV.

One of the things you can do this Fourth of July when you have friends and family gathered for the barbeque of burgers, hot dogs, and ribs is to print out the Declaration and have you family members and friends each read aloud a portion of the document. I did this at my annual birthday party over the weekend and it was not only informative and educational, but was a fun experience — especially when they got to the part containing the grievances against the King George III.

After reading the grievances some discussion evolved on the listed grievances and how these same grievances can be adapted to what the government is doing to its citizens today. Here are a few examples.

Before citing the examples lets preface then with the remaining section of the preamble:

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect [sic] their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn [sic], that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.”

“He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

Look at how the present administration refuses to enforce laws such as our current immigration laws and how the Justice Department refused to enforce the legally enacted Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) signed into law by Bill Clinton.

“He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.”

Just look at what the federal government is doing to states with the passage of ObamaCare and how governors are being pressed to pay for more and more towards Medicaid. Also how the federal government is attempting to force states to accept federal gun and drug laws.

“He has endeavoured [sic] to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.”

Just look at how the federal government has opposed the states enforcement of our immigration laws through the actions of the Justice Department using the power of the federal courts and Homeland Security by refusing to put forth the resources to control illegal immigration. Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution states:

“The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion; and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) against domestic violence.”

Millions of illegals have and are crossing our southern border as they invade the states of California, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico while the executive branch does little to prevent this as the Democrats are looking for adding these illegals to their voting bloc.

“He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass [sic] our people, and eat out their substance.”

Over the past decades the administrative state has created hundreds of new czars and regulators to hassle, badger, and bully citizens. The EPA, Department of Agriculture, Department of Education, NSA, IRS, and Homeland Security have put forth thousands of regulations without the consent of Congress. They have mandated regulations for K-12 public schools overriding the will of states and local school boards. They have told us what light bulbs and toilets we can use. The NSA is collecting your personal data on your phone calls and e-mails. The IRS imposes illegal regulation of political opponents of the Obama administration. The Obama administration is waging a war against Christians who do not approve of gay marriage, abortion or the requirements for birth control and abortifacient pharmaceutical drugs for girls as young as 13-years of age without parental consent as mandated in ObamaCare. It has even reached the point of absurdity where the Department of Agriculture is demanding a children’s magician to submit a disaster plan for his rabbit. The new regulation became effective Jan. 30, 2012 without the consent of Congress.

“He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation.”

The current administration and certain members of the U.S. Supreme Court are now referring to foreign laws to interpret our Constitution and Bill of Rights. As Associate Justice Antonin Scalia stated in his dissent to the recent DOMA decision

“The majority must have in mind one of the foreign constitutions that pronounces such primacy for its constitutional court and allows that primacy to be exercised in contexts other than a lawsuit.”

“For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent”

Today our tax code is so complex it obfuscates many of the taxes we pay the federal government. Also the administration through its regulatory agencies imposes thousands of fees on unsuspecting citizens. How about the carbon taxes and the taxes on your telephone and cable TV? Or the taxes on your electric bill to pay for those who do not have enough money to afford electricity?

I am sure you can find many examples of current actions of the federal government that pertain to the grievances I have cited.

Jefferson’s conclusion to the Declaration states:

“We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these

Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

I wonder how many of today’s crop of politicians are willing to pledge their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor in the cause of liberty.

When and if you do decide to have a communal reading of the Declaration at your Fourth of July BBQ here are nine things you may not know about our Declaration of Independence — things that will no doubt impress your family and friends:

1. The Declaration of Independence wasn’t signed on July 4, 1776.

On July 1, 1776, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, and on the following day 12 of the 13 colonies voted in favor of Richard Henry Lee’s motion for independence. The delegates then spent the next two days debating and revising the language of a statement drafted by Thomas Jefferson. On July 4, Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence, and as a result the date is celebrated as Independence Day. Nearly a month would go by, however, before the actual signing of the document took place. First, New York’s delegates didn’t officially give their support until July 9 because their home assembly hadn’t yet authorized them to vote in favor of independence. Next, it took two weeks for the Declaration to be “engrossed”—written on parchment in a clear hand. Most of the delegates signed on August 2, but several—Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean and Matthew Thornton—signed on a later date. (Two others, John Dickinson and Robert R. Livingston, never signed at all.) The signed parchment copy now resides at the National Archives in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom, alongside the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

2. More than one copy exists.

After the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the “Committee of Five”—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert R. Livingston—was charged with overseeing the reproduction of the approved text. This was completed at the shop of Philadelphia printer John Dunlap. On July 5, Dunlap’s copies were dispatched across the 13 colonies to newspapers, local officials and the commanders of the Continental troops. These rare documents, known as “Dunlap broadsides,” predate the engrossed version signed by the delegates. Of the hundreds thought to have been printed on the night of July 4, only 26 copies survive. Most are held in museum and library collections, but three are privately owned.

3. When news of the Declaration of Independence reached New York City, it started a riot.

By July 9, 1776, a copy of the Declaration of Independence had reached New York City. With hundreds of British naval ships occupying New York Harbor, revolutionary spirit and military tensions were running high. George Washington, commander of the Continental forces in New York, read the document aloud in front of City Hall. A raucous crowd cheered the inspiring words, and later that day tore down a nearby statue of George III. The statue was subsequently melted down and shaped into more than 42,000 musket balls for the fledgling American army.

4. Eight of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence were born in Britain.

While the majority of the members of the Second Continental Congress were

5. One signer later recanted.

Richard Stockton, a lawyer from Princeton, New Jersey, became the only

6. There was a 44-year age difference between the youngest and oldest signers.

The oldest signer was Benjamin Franklin, 70 years old when he scrawled his name on the parchment. The youngest was Edward Rutledge, a lawyer from South Carolina who was only 26 at the time. Rutledge narrowly beat out fellow South Carolinian Thomas Lynch Jr., just four months his senior, for the title.

7. Two additional copies have been found in the last 25 years.

In 1989, a Philadelphia man found an original Dunlap Broadside hidden in the back of a picture frame he bought at a flea market for $4. One of the few surviving copies from the official first printing of the Declaration, it was in excellent condition and sold for $8.1 million in 2000. A 26th known Dunlap broadside emerged at the British National Archives in 2009, hidden for centuries in a box of papers captured from American colonists during the Revolutionary War. One of three Dunlap broadsides at the National Archives, the copy remains there to this day.

8. The Declaration of Independence spent World War II in Fort Knox.

On December 23, 1941, just over two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the signed Declaration, together with the Constitution, was removed from public display and prepared for evacuation out of Washington, D.C. Under the supervision of armed guards, the founding document was packed in a specially designed container, latched with padlocks, sealed with lead and placed in a larger box. All told, 150 pounds of protective gear surrounded the parchment. On December 26 and 27, accompanied by Secret Service agents, it traveled by train to Louisville, Kentucky, where a cavalry troop of the 13th Armored Division escorted it to Fort Knox. The Declaration was returned to Washington, D.C., in 1944.

9. There is something written on the back of the Declaration of Independence.

In the movie “National Treasure,” Nicholas Cage’s character claims that the back of the Declaration contains a treasure map with encrypted instructions from the founding fathers, written in invisible ink. Unfortunately, this is not the case. There is, however, a simpler message, written upside-down across the bottom of the signed document: “Original Declaration of Independence dated 4th July 1776.” No one knows who exactly wrote this or when, but during the Revolutionary War years the parchment was frequently rolled up for transport. It’s thought that the text was added as a label.

No comments:

Post a Comment