“Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise. For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore, security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expense and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others” — Thomas Paine, Common Sense, 1776

Yesterday we learned that President Mohammed Morsi was removed from office, placed under house arrest, and the new constitution suspended by the Egyptian military. After rioting in the streets two years ago great hope was had for Egypt when the dictator president Mubarak was removed. This was labeled the “Arab Spring” by our government and media. Soon afterward a new constitution was adopted and a new president elected — Mohammed Morsi — with the support of the military and the Muslim Brotherhood.

As things worsened in Egypt with unemployment approaching 25% and food

For Islamists, however, the idea of Morsi stepping down is an inconceivable infringement on the repeated elections they won since Mubarak's fall, giving them not only a longtime Brotherhood leader as president but majorities in parliament.

Like most revolutions that begin in the streets or that are influenced by outside forces the Arab Spring failed and will continue to fail. This is because these revolutions are usually based and focused on things people want not on the principles of liberty. They are dissatisfied with the rulers they have, usually because of tyrannical polices and economic conditions. The ruling class is concerned about the tyranny and the poor are concerned about bread.

If there is one extremely deceptive aspect of the American Revolution, it is that the Founding Fathers made revolution look easy. Since that fateful day, over two centuries ago, revolutions have ruffled across the globe, many claiming to follow in the ideals of the American Founders, or claiming to take their principles to a higher level. Almost none of them succeeded. None succeeded as fully. Quite often the result was a tyranny darker than the one overthrow.

Four things are necessary for a successful revolution:

1) The old order must be rotten

2) The revolutionary cause must offer improvement

3) Circumstances must be providential

4) The revolutionaries must be worthy

The first requirement is quite often easy to meet. As a general rule, governments are rotten. Some more than others; but it is the rare nation that is blessed with good government. The question is: Is the government rotten enough to merit a struggle, particularly an armed one?

In the case of the American Revolution, the British government was rotten and corrupt to the core. Our school books dumb down the cause to mere taxes, but it is more than that. British laws had put a stranglehold on the American economy, with the intent of making America nothing more than a dumping ground for British manufactures. Trade with the French or Spanish was forbidden.

To the untutored this may seem like nothing more than a protectionist policy; but in the seventeenth century this policy had reduced Scotland to poverty and Ireland to a slavish, starving state of destitution; all by design. The rest of the Empire existed only to make London rich. On top of all of this, the colonists had no representation in the Parliament to correct the matter. Not that it would have mattered much with such a corrupt legislature.

Franklin, who had spent some time in the British Isles, had seen the devastation wrought by these policies.

Franklin toured Ireland in 1771 and was astounded and moved by the level of poverty he saw there. Ireland was under the trade regulations and laws of England, which affected the Irish economy, and Franklin feared that America could suffer the same plight if Britain's exploitation of the colonies continued.

More than anything else, Franklin saw how London Bankers, through the Currency Act, forced American colonies to stop issuing their own currency; and required them to take loans at interest. This caused an immediate depression in the colonies.

Franklin saw corruption and influence peddling that sickened him. He knew that America was slated to become nothing more than England's useful doormat. Franklin had gone to England in 1757 as a cheerleader for the British Empire. He would return to the colonies in 1775 as a revolutionary.

The American Revolution met the first requirement. The old order was rotten.

The second requirement is to offer improvement.

One would be surprised how many revolutions do not. Quite often governments can be overthrown merely to exchange power, not improve the situation. This or that tribe feels oppressed, and overthrows the ruling tribe; but no improvement is sought. The underclass and ruling class have merely exchanged places. This is quite typical in the Arab and African world. The present Syrian Civil War between Sunni and Shia is just such a struggle. No matter who wins, the object is to oppress the other side.

In other cases, governments can be overthrown to prevent improvement. This is quite common in Latin America where right or left wing groups have been known to overthrow governments rather than have them proceed with reform. In such cases, the maintenance of tyranny is sought.

In Europe, governments were overthrown to institute murderous totalitarian regimes far worse than the previous order; often in the name of class or ethnic struggle.

In all these cases, these countries would have been better without such revolutions, if only to prevent unnecessary bloodshed, and quite often to prevent a genuine horror.

The second requirement of improvement is rarely met. The Belgians met it in

In America, however, the colonists had a clear vision of liberty; and what it meant. They had enough experience with self-government to know that they could indeed run things better than the British. They had been schooled in the writings of Locke to know how a good government should be framed.

The third requirement is circumstance. There are many fine worthy peoples who have never achieved independence and liberty for lack of providential circumstance.

The Basque come to mind. They are an industrious people who greatly outperform Spain proper. Their per capita output is equal to Germany's. In the Middle Ages, they had a wrested a degree of local autonomy from Spanish kings and ran their provinces like republics guided by the fueros (laws). Moreover, they were amazingly egalitarian with their women; always a sign of high civilization. Devoutly Christian, the Basque — mostly part of the forces fighting Franco — refused to embrace the communist atheism rampant in the Spanish Republican ranks; but remained proudly Catholic.

After Franco's victory, it was the Basque country which regularly protested against his fascist rule. The General Strike of 1947 being a famous example.

Yet, this noble people is stuck between France and Spain. They will almost certainly never rise above autonomy, though they certainly deserve more. Likewise, can anyone doubt that if it were not the circumstance of adjacent geography, all of Ireland would be free of British rule by now?

Americans of the Revolution were blessed with natural wealth, a century and a half of practice in colonial self-government, and a history of self-reliance when Britain ignored them, as it did during their Cromwellian Civil War. Most of all, the three thousand miles between America and Britain was a game-changer.

America's circumstances were providentially blessed.

The fourth, and most important requirement, is the quality of men. Most revolutions are run by thugs or benighted intellectuals. Mussolini, Stalin, Castro, the Assads of Syria, etc. Worse yet, they often depend on illiterate masses following them.

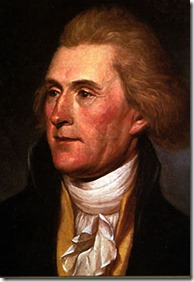

The Americans of the Revolution were the most unique people in world history. Literate, self-reliant, and moral at levels that is hard for us to conceive of today. They were probably the most biblically educated people in world history. Even the unbelieving Tom Paine would frame his pamphlet, Common Sense, arguing for revolution based on the Old Testament passages.

Contrary to popular belief, America was not one-third revolutionary, one-third neutral, and one-third Tory. In actuality, ninety percent of the population was in favor on Independence, to some degree or another. The American people were of a rare caliber of excellence, unity, and character.

When one looks at other revolutions in history, no one other people comes close.

Cromwell, who claimed to be setting up a Christian Commonwealth in 17th century Britain, dismissed the Parliament, and assumed the mantle of Lord Protector; which is a fancy name for dictator — a Protestant Ayatollah.

Washington, on the other hand refused a similar prospect when Army officers at Newburgh offered to deliver the new American government into his hands. He would not take the path of Caesar, Cromwell, or the subsequent Napoleon. The Europeans were so astounded by Washington's character that he would be honored by all as a giant of history, even in his lifetime; even by the British. Upon news of his death, Napoleon had the French navy fire volleys in his honor.

This year, Americans will again gather on the public square not just to celebrate and recite, but to seriously reflect on the founders' hallowed words. Millions today fear the nation is heading in the wrong direction, if not rushing headlong toward calamity. Sensing the urgent need for a dramatic "mid-course" correction, citizens should search for guidance in the doctrines that have served so many, so well, for so

Founding principles are fundamental. They allow us to reach the root of our difficulties rather than just deal in mere policy details. They make possible deep-seated, encompassing political reform. Unfortunately, no number of readings of the founding documents will furnish any satisfactory answers to the basic queries. Neither Jefferson's Declaration nor the Framers' Constitution sufficiently spells out the strict bounds of public power, the exact extent and limit of the law. The basic questions are these: What should government do for the governed? And what must the governed be expected to do for themselves? When can, when must, a people say to their political leaders this far, and no farther? How limited must limited government be? When did the country first go off course? And how did we get from that day to this?

Nothing so illustrates the point as much as the 2013 State of the Union Address. "What makes us exceptional," President. Obama asserted, "is our allegiance to an idea articulated in a declaration made more than two centuries ago: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.'"

Precisely how is this abstract principle to be applied? It's anybody's guess. For, "when times change, so must we," Why is that? Because "fidelity to our founding principles will require new responses to new challenges; because preserving our individual freedoms ultimately requires collective action?" Mr. Obama once pledged to effect a fundamental transformation of our political order. And so, in the Union he envisions, the state would "harness new ideas and technology to remake our government that is what will give real meaning to our creed." Just how much change can a founding creed carry before it shatters into thousands of unmanageable policy pieces?

Hearing the president, one might conclude that the Declaration of Independence says whatever anyone wants it to say. But that isn't so. Jefferson's revolutionary manifesto clearly enunciates the precise limit of government's "lawful" power. The needed guidance is there, but to grasp it fully one must learn to read between the lines. Etched into the revolutionary parchment, if only in invisible ink, is a grander, more comprehensive political vision. For, all other influences notwithstanding, the patriots of the Revolution, the Framers of the Constitution, the Federalists who supported, and the Antifederalists who opposed its ratification, were all committed to a set of principles nowhere more fully enunciated than in the writings of John Locke.

What kept Locke's memory alive some 70 years after his passing? Writing during the turbulent years leading up to England's Glorious Revolution, Locke

But with what should the old guards be replaced? Here, too, Locke mentored the Americans. Locke imagined a time without government, a "state of nature." But he really was describing "the state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man (II, §4)." Why is that? Because of certain basic commitments Locke and Jefferson shared. The Declaration thus declares, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." For Locke, "there is nothing more evident than that creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another without subordination or subjection" (II, §6).

You see, "the state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges everyone, and reason which is that law, teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions." (II, §6). As men are created equal, so they are "endowed with certain "unalienable" rights. Locke designated these "Life, Liberty and Property." Jefferson replaced property with "the Pursuit of Happiness." All understood that happiness is not possible where there is no right to gain, keep, use, and dispose of material possessions.

What comes next is pivotal. Jefferson explains that it is "to secure these

The answer will be found in exposing one additional right Locke finds in the natural make-up of man: the right of self-defense. If men could not defend their persons and possessions from being violated, in the prepolitical state of nature, in reality, they would have no rights at all. Upon establishing civil government, then, individuals do not surrender their fundamental rights. It is to better protect their lives, liberties, and possessions that they grant government the right to rule over them. The original right of self-defense is transformed into government's power to defend all the rights of every single citizen. Citizens pledge not to take the law into their own hands, not to become vigilantes, but to rely on the rule of law and the institutions of government to prevent or justly punish any assault on men's liberties from all threats foreign and domestic. For its part, government erects effective military, intelligence, police, judicial and correctional institutions to assure individuals the enjoyment of what is already theirs. And that it is all political leadership is authorized to do. Locke himself was plain as daylight on the point:

“For nobody can transfer to another more power than he has in himself; and no Body has an absolute Arbitrary Power over any other, to take away the Life or Property of another and having in the State of Nature no Arbitrary Power over the Life, Liberty or Possessions of another, but only so much as the Law of Nature gives him to the preservation of himself; this is all he doth, or can give up to the Commonwealth so that the Legislative can have no more than this. (XI, § 135).”

No one had the right to restrain another from doing as he or she pleased or to abscond with what another earned by the sweat of his brow. Having no such right, in the state of nature, no number of organized special interests or humanitarian pleaders can affect such a transfer. Government was designed to serve as a Protector. The moment it begins acting not to protect (the interests of all), but rather to assist (some, and always at the expense of others), government transforms itself from Protector to Provider. And what it provides, might as well be called welfare (whether offered to rich or poor, young or old, healthy or sick, family farmer or "fat-cat" financier).

The Social/Corporate welfare complex and the Lockean/Jeffersonian conception of ordered liberty/laissez faire form two mutually exclusive social visions. From the founders' perspective, the wide range of social services, business subsidies, and sundry other privileges doled out over the past two centuries constitute no lawful exercise of political power. (The ObamaCare mandate, compelling every American to purchase a health insurance policy deemed "acceptable" by Washington hardly counts as the first "unprecedented" assault on individual liberty suffered by the people.)

To champion the nation's founding principles is to commit to a downsizing of government the likes of which can barely be imagined, in today's climate. Who in America is prepared to handle the whole truth and nothing but or commit to so radical a cause? Who on talk radio would dare hint of mounting a righteous crusade of abolition against the welfare principle, as such? Which Tea Party candidate will run for office pledging to slash his constituents' benefits and put the civil servants in his district or state out to pasture?

It's an open question whether any lesser course will spare the nation the calamitous consequences that eventually catch up to ill-begotten causes. But this little exercise allows the July 4th revelers to more clearly appreciate: (1) just when the country first veered off the founding course; and (2) how she got from that day to this.

By Locke's reckoning, the fateful shift came with the second bill signed into law by the nation's first president. The Tariff Act of 1789, in addition to raising revenue, something certainly sanctioned by the Constitution, authorized Congress to "encourage domestic manufactures." It could impose a "protective" tariff, raising the price of goods coming from Europe, inviting retaliatory measures and curtailing the trans-Atlantic trade, but not without raising consumer prices for farmers and planters and depriving many of those who made their living in the seafaring trades of their livelihoods. How did the country get from that day to this? Consider this principle:

Once a nation decides that some of its citizens have a right not to go out and get, but to sit still and be given, it finds itself torn by two questions: Just who should be given and exactly how much should they get? There's only one answer: Politics. As the demands for benefits and privileges grow, so must the supply. There's no limit to what citizens, in the crucible of time, may consider themselves "entitled" to. After that, it's politics all the way down.

Two hundred thirty seven years ago, our forefathers sat in a hot room with closed windows arguing over the future of the thirteen colonies they represented. For a while they had thought of reconciliation with their motherland. But over time it became clear that neither King nor Parliament were interested in anything other than submission.

These fifty-six men did what had not been done before them.

They outlined their grievances on paper, declared their independence, and signed their names so both King and Parliament would know who the traitors were. The act was treason punishable by death. Some of them did die. Some were bankrupted. Many lost their homes and property. Some saw their wives and children taken and abused. But none recanted. All held firm.

237 years later we view the unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America in the abstract. The grievances are distant if not surreal. But it was very real to them.

The United States of America today stands 69 years removed from D-Day.

D-Day was 79 years from the end of the Civil War, and 81 years removed from Gettysburg, which we are now 150 years separated from in time and history.

The beginning of the Civil War was 85 years from 1776 and only 72 years from the constitution being enacted.

The Revolution was only 88 years from the Glorious Revolution — a revolution from which we are separated by a chasm of 325 years.

It was the Glorious Revolution that so influenced our John Locke and our Founders. It was not abstract to them. It was not far removed. It was an event in the lifetimes of some of their grandparents. Parliament’s supremacy was asserted. The British subjects became citizens and acquired certain rights under the Bill of Rights of 1689 while others from the Magna Carta were reinforced. Among the rights derived from the Glorious Revolution were prohibitions on taxation without representation in Parliament, prohibitions on a standing army, the right to petition the King without prosecution, the prohibition on dispensing with Acts of Parliament, and the prohibition of fines and forfeitures before convictions of crimes.

The American colonists saw themselves as British citizens, not just subjects. They saw themselves as heirs to a Glorious Revolution and the Bill of Rights that sprang therefrom. These events were not even a century beyond them. They wanted their rights and when King and Parliament would not grant them those rights they rebelled. As Jefferson stated in the Declaration:

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect [sic] their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn [sic], that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.”

The colonists — the revolutionaries — did not want something new, but something old. By 1776, eighty-eight years after their Glorious Revolution, the colonists realized they would have to throw off the old form of government for something new in order to gain back those rights they realized neither Crown nor Government acknowledged they had. To King George and the men of the British Parliament, these were colonists, a class of men and women not heirs to the Glorious Revolution and most certainly not true British citizens.

The colonists engaged in a conservative revolution — a revolution not for something wholly new, but for something 88 years old. They only rebelled for “new Guards for their future security” when neither King nor Parliament would grant them what they thought they already had: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

What we find today to be so abstract — gun rights written into our Constitution prohibition on quartering soldiers, checks and balances and clear limits on power drawn up by men deeply skeptical of themselves and others with power — were not abstract notions to our Founders. They were real. They were present. Most importantly, they were worth fighting for and, if need be, dying for.

More than two centuries now separate us from our Founding Fathers. The liberties they fought for were liberties to thrive absent the heavy hand of government. These days now most often the recitation of liberties from the people are those things they can do so long as government provides a safety net to ensure a soft landing in the event of failure.

Failure to our Founders meant hanging. Would you this day pledge your life and be willing to die for your cause? Would you?

Those fifty-six men were willing to.

In the heat of July in room full of flies with no circulating air those men debated the future of the colonies. On July 2nd, by unanimous declaration, they proclaimed the colonies the United States of America, setting the date of adoption of the declaration as July 4, 1776. The unity then was one of purpose at the time, not unity as one nation. But that would come.

In even hotter August those men would go to Philadelphia to sign their names and make public the declaration of their treason.

“And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

What they were prepared to lose remains to this very day our gain. We are 237 years removed from that time, but we should all pray we never remove ourselves so far from the spirit of 1776.

“..appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.”

All revolutions throughout history, with the exception of the American Revolution, turned out badly within a few years due to the lack of Lockean/Jeffersonian principles. The French Revolution turned into a reign of terror as the people began to indulge in class warfare. It became a war of the have-nots against the haves. The Russian Revolution was doomed from the beginning as it was based on the principles of Karl Marx — principles of class warfare and the supremacy of the collective. Stalin killed millions as displaced the kulaks from their farms and turned kulak against kulak. All rights came from Moscow, not God.

The numerous revolutions in Mexico, Latin and South America were based on bread, land, and jobs. Even the great Simon Bolivar was no Jefferson. These countries were steeped in Spanish culture where the monarchy was absolute. There were no Lockes, Montesquieus, Smith in Spain’s history for people to draw on. They attempted to copy parts of our Declaration and Constitution but they had no real deep understanding of the words and their meanings. What the people (peasants and farmers) wanted was land and bread. When a leader arose who would promise this he became the next dictator until he was deposed by the next revolution or the ruling oligarchies.

The American Revolution was different. It was promulgated by men were educated in the rights of the British sine the Glorious Revolution. They were farmers, merchants, planters, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and everyday folks who had land and bread. Many were wealthy and some not. The one common thread was that they all wanted the rights proclaimed by John Locke. They were not interested in obtaining or increasing power. They wanted to be left alone to pursue their dreams without stomping the dreams of their neighbor. They wanted nothing from their neighbor except an appreciation of their rights. They believed government’s only role was to protect those rights from foreign and domestic threats. They realized that would cost everyone so they agreed to pay for that government. They also adopted a Constitution based on the principles of the Declaration that would enumerate and limit the power of the central government while giving all powers not so enumerated to the people.

Today we, as a people, have drifted away from those founding principles as we look to the central government for property and sustenance. As we demand more free stuff at the expense of others we trample of their rights, but we also abdicate some our rights along the way. This happens as we give more and more power to the central government and we become a nation ruled by men, not by our laws as enacted to preserve our founding principles.

When Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, he used language that has become iconic.

He wrote that we are endowed by our Creator with certain inalienable rights,

Not only did he write those words, but the first Congress adopted them unanimously, and they are still the law of the land today.

By acknowledging that our rights are inalienable, Jefferson’s words and the first federal statute recognize that our rights come from our humanity — from within us — and not from the government.

The government the Framers gave us was not one that had the power and ability to decide how much freedom each of us should have, but rather one in which we individually and then collectively decided how much power the government should have. That, of course, is also recognized in the Declaration, wherein Jefferson wrote that the government derives its powers from the consent of the governed.

To what governmental powers may the governed morally consent in a free society? We can consent to the powers necessary to protect us from force and fraud, and to the means of revenue to pay for a government to exercise those powers. But no one can consent to the diminution of anyone else’s natural rights, because, as Jefferson wrote and the Congress enacted, they are inalienable.

Just as I cannot morally consent to give the government the power to take your freedom of speech or travel or privacy, you cannot consent to give the government the power to take mine.

This is the principle of the natural law: We all have areas of human behavior in which each of us is sovereign and for the exercise of which we do not need the government’s permission. Those areas are immune from government interference.

That is at least the theory of the Declaration of Independence, and that is the basis for our 237-year-old American experiment in limited government, and it is the system to which everyone who works for the government today pledges fidelity.

Regrettably, today we have the opposite of what the Framers gave us. Today we have a government that alone decides how much wealth we can retain, how much free expression we can exercise, how much privacy we can enjoy. And since the Fourth of July 2012, freedom has been diminished.

In the past year, all branches of the federal government have combined to diminish personal freedoms, in obvious and in subtle ways.

In the case of privacy, we now know that the federal government has the ability to read all of our texts and emails and listen to all of our telephone calls — mobile and landline — and can do so without complying with the Constitution’s requirements for a search warrant (Fourth Amendment).

We now know that President Obama authorized this, federal judges signed off on this, and select members of Congress knew of this, but all were sworn to secrecy, and so none could discuss it. And we only learned of this because a young whistleblower risked his life, liberty and property to reveal it.

In the past year, Obama admitted that he ordered the CIA in Virginia to use a drone to kill two Americans in Yemen, one of whom was a 16-year-old boy. He did so because the boy’s father, who was with him at the time of the murders, was encouraging militants to wage war against the U.S.

He wasn’t waging war, according to the president; he was encouraging it.

Simultaneously with this, the president claimed he can use a drone to kill whomever he wants, so long as the person is posing an active threat to the U.S., is difficult to arrest and fits within guidelines that the president himself has secretly written to govern himself.

In the past year, the Supreme Court has ruled that if you are in police custody and fail to assert your right to remain silent, the police at the time of trial can ask the jury to infer that you are guilty. This may seem like a technical ruling about who can say what to whom in a courtroom, but it is in truth a radical break from the past.

Everyone knows that we all have the natural and constitutionally guaranteed right to silence. And anyone in the legal community knows that judges for generations have told jurors that they may construe nothing with respect to guilt or innocence from the exercise of that right. (Fifth Amendment)

No longer. Today, you remain silent at your peril.

In the past year, the same Supreme Court has ruled that not only can you be punished for silence, but you can literally be forced to open your mouth. The court held that upon arrest -- not conviction, but arrest — the police can force you to open your mouth so they can swab the inside of it and gather DNA material from you.

Put aside the legal truism that an arrest is evidence of nothing and can and does come about for flimsy reasons; DNA is the gateway to personal data about us all. Its involuntary extraction has been insulated by the Fourth Amendment’s requirements of relevance and probable cause of crime.

No longer. Today, if you cross the street outside of a crosswalk, get ready to open your mouth for the police.

The litany of the loss of freedom is sad and unconstitutional and irreversible. The government does whatever it can to retain its power, and it continues so long as it can get away with it. It can listen to your phone calls, read your emails, seize your DNA and challenge your silence, all in violation of the Constitution.

Bitterly and ironically, the government Jefferson wrought is proving the accuracy of Jefferson’s prediction that in the long march of history, government grows and liberty shrinks. Somewhere Jefferson is weeping.

We have strayed from the path our Founders forged 237 years ago. Under the Constitutional Republic they created after the Revolutionary War, the United States has prospered over the centuries beyond the founding generation’s wildest dreams; however, we are wandering further from those very Constitutional principles that enabled us to thrive.

Our Founders developed an ingenious system of checks and balances, which

But over the years, power has shifted from the local level to the federal government, where bitter partisanship clogs the mechanisms of that ingenious system by which we might begin to repair.

If history is a guide, Washington would not give up on our Constitutional Republic now — he would fight to return it to its proper functioning. And he would begin by rallying the electorate. As he did during his time, he would extol us to replace wayward politicians with leaders who will act in the best interests of the country instead of their party.

The evils of modern politics were foreshadowed by the prescient words of the founding generation.

Washington, our nation’s first and only president with no declared party allegiance, was perhaps the most weary of the harms caused by uncompromising political factions.

With the ink on the Constitution barely dry, the nation fractured into competitive political parties.

President Washington derided these factions as “a fire not to be quenched, demanding a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.” He believed that they “agitated the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindling]the animosity of one part against another.”

Fortuitously, Washington prescribed how we might fight that fire: “by force of public opinion.”

James Madison echoed this sentiment in Federalist 10, where he suggested

Our Founders charged us, the public, with the responsibility to elect those representatives that will rightfully uphold our Constitution — and reject those who place their own power and parties over the good of the nation. And what if we cannot find any good candidates? Run for office. It is our civic duty.

On this July Fourth, we find ourselves in a great country that is mired by politicians who seem to expend more resources fighting one another than adhering to our Constitution.

The United States government was never meant to be a “team sport” of Democrats vs. Republicans.

Our forward thinking Founders have gifted us with advice from the grave: we must beat back the partisanship with our votes and civic involvement, and install principled leaders, as our Founders were.

If we are to lead our nation towards those core Constitutional principles that have enabled us to prosper, we do so “by force of public opinion.”

“The foundation of our Republic was not laid in the gloomy age of Ignorance and Superstition, but in an era when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined,” Washington wrote in 1783, “At this auspicious period, the United States came into existence as a Nation, and if their Citizens should not be completely free and happy, the fault will be entirely their own.”

In 237 years we have journeyed many steps backwards on the path to life, liberty, property. With that said it is still possible to reverse this course if we and our fellow citizens can educate ourselves in those sacred principles and begin to restore self-government. This will require sacrifice and hard work. The question one must ask is; are we willing to sacrifice our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor to so?

In the meantime we should celebrate our Declaration and revolution in the manner prescribed by John Adams in his famous letter of July 3, 1776, in which he wrote to his wife Abigail what his thoughts were about celebrating the Fourth of July:

“The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews [sic], Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more. You will think me transported with Enthusiasm but I am not. I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure, that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States. Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory. I can see that the End is more than worth all the Means. And that Posterity will triumph [sic] in that Days Transaction, even altho [sic] We should rue it, which I trust in God We shall not.”

Thank you so much for giving everyone such a splendid opportunity to discover important secrets from this site.

ReplyDeleteIt is always very sweet and full of fun for me personally and my office colleagues to

visit your blog minimum thrice in a week to see the fresh guidance you will have.

And definitely, I'm so always amazed for the fabulous creative

ideas served by you. Some two points in this posting are absolutely the most effective we've had.

Visit my site :: 오피사이트

(jk)