"Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people; and not for profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men." — John Adams

May 10th was the 143rd anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. On this day in 1869, the presidents of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads meet in Promontory, Utah, and drive a ceremonial last spike into a rail line that connects their railroads. This made transcontinental railroad travel possible for the first time in U.S. history. No longer would western-bound travelers need to take the long and dangerous journey by wagon train, and the West would surely lose some of its wild charm with the new connection to the civilized East. Nor would goods have to travel by ship on the odious journey around the Cape Horn and the Straits of Magellan to reach San Francisco.

Since at least 1832, both Eastern and frontier statesmen realized a need to connect the two coasts. It was not until 1853, though, that Congress appropriated funds to survey several routes for the transcontinental railroad. The actual building of the railroad would have to wait even longer, as North-South tensions prevented Congress from reaching an agreement on where the line would begin.

One year into the Civil War, a Republican-controlled Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act (1862), guaranteeing public land grants and loans to the two railroads it chose to build the transcontinental line, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific. With these in hand, the railroads began work in 1866 from Omaha and Sacramento, forging a northern route across the country. In their eagerness for land, the two lines built right past each other, and the final meeting place had to be renegotiated.

The original Act's long title was “An Act to aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes”. It was based largely on a proposed bill originally reported six years earlier on August 16, 1856, to the 34th Congress by the Select Committee on the Pacific Railroad and Telegraph. Signed into law by the President Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, the 1862 Act authorized extensive land grants in the Western United States and the issuance of 30-year government bonds (at 6 percent) to the Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad (later the Southern Pacific Railroad) companies in order to construct a transcontinental railroad. Section 2 of the Act granted each Company contiguous rights of way for their rail lines as well as all public lands within 200 feet on either side of the track.

Section 3 granted an additional 10 square miles of public land for every mile of grade except where railroads ran through cities or crossed rivers. The method of apportioning these additional land grants was specified in the Act as being in the form of "five alternate sections per mile on each side of said railroad, on the line thereof, and within the limits of ten miles on each side" which thus provided the companies with a total of 6,400 acres for each mile of their railroad. (The interspersed non-granted area remained as public lands under the custody and control of the U.S. General Land Office.) The U.S. Government Pacific Railroad Bonds were authorized by Section 5 to be issued to the companies at the rate of $16,000 per mile of tracked grade completed west of the designated base of the Sierra Nevadas and east of the designated base of the Rocky Mountains. Section 11 of the Act provided that the issuance of bonds "shall be treble the number per mile" (to $48,000) for tracked grade completed over and within the two mountain ranges (but limited to a total of 300 miles at this rate), and doubled (to $32,000) per mile of completed grade laid between the two mountain ranges.

The Act also specified that the gauge of the track (the distance between the inside flange of opposing rails) be standardized at 4 feet, 8.5 inches. This is the standard gauge used for all railroads and urban rail today. Until the approval of the Transcontinental Railroad there were tracks of varying gauges throughout the United States. This caused a lack of standards in rolling stock and the inability to connect various lines with one another.

The U.S. Government Bonds constituted a lien upon the railroads and all their fixtures, and all were repaid in full (with interest) by the companies as and when they became due. Section 10 of the 1864 amending Act Statutes at Large, additionally authorized the two companies to issue their own "First Mortgage Bonds" in total amounts up to (but not exceeding) that of the bonds issued by the United States, and that such company issued securities would have priority over the original Government Bonds.

From 1850-1871, the railroads received more than 175 million acres of public land — an area more than one tenth of the whole United States and larger in area than Texas.

Railroad expansion provided new avenues of migration into the American interior. The railroads sold portions of their land to arriving settlers at a handsome profit. Lands closest to the tracks drew the highest prices, because farmers and ranchers wanted to locate near railway stations.

Harsh winters, staggering summer heat, Indian raids and the lawless, rough-and-tumble conditions of newly settled western towns made conditions for the Union Pacific laborers — mainly Civil War veterans of Irish descent--miserable. The overwhelmingly immigrant Chinese work force of the Central Pacific also had its fair share of problems, including brutal 12-hour work days laying tracks over the Sierra Nevada Mountains. On more than one occasion, whole crews would be lost to avalanches, or mishaps with explosives would leave several dead.

For all the adversity they suffered, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was not only a great feat of engineering; it was also needed for the economic expansion of the United States. It connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and made us one country. We now had a unified nation connected by a ribbon of steel and the telegraph lines that ran alongside of the railroad.

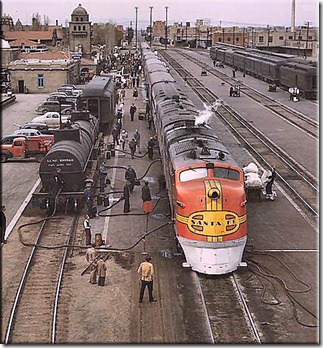

For years the nation traveled and shipped on rails. It was the primary means of intercontinental transportation and communication. There were high profile trains like the New York Central’s Empire State and the Santa Fe’s Super Chief. A passenger could travel from New York City to Los Angeles, via Chicago, in comfort and elegance while enjoying the scenery of the great southwest from the glass-domed observation cars.

Two things brought an end to passenger rail travel in the United States — the interstate highway system and the growth and safety of air travel.

Now we have a new resurgence in passenger rail service, a resurgence the railway companies want no part of. We have AMTACK, a government owned corporation, that runs passenger trains at a billion dollar loss each year — money out of the taxpayer’s pocket. We also have a federal government that wants to push passenger rail service at the expense of the taxpayers — spending money we don’t have to finance something called High-Speed Rail. (See: Does California Really Need High Speed Rail? And Why High Speed Rail is Obama's Fantasy.)

The latest example of this fantasy is something called the DesertXpress, a proposal to build a privately funded high-speed rail passenger train from Victorville, California, to Las Vegas, Nevada.

The proposal would provide an alternative to automobile travel between the Los Angeles area to Las Vegas along Interstate 15 as well as an alternative to airline travel. Interstate Highway 15 is a direct automobile route between the two regions and carries heavy traffic. Greyhound buses cover the route in between five and seven hours, while automobiles take around four hours. Currently, there is no passenger train service to Las Vegas. Amtrak last operated passenger train service to Las Vegas in 1997 on its Desert Wind route, which was cancelled due to budget cuts.

The city of Victorville was selected as the location for the westernmost terminal since extending the train line farther into the Los Angeles basin through the Cajon Pass would be prohibitively expensive. Victorville is about 40 mi from Riverside, where a station was proposed for the California high-speed rail line. The station would include free parking and through-checking of baggage straight to the Las Vegas Strip resorts. A future extension would include a new link to the California High-Speed Rail station in Palmdale.

The train would travel at speeds of up to 150 mph and would make the 186

Richard N. Velotta writes in the Las Vegas Desert Sun in February, 2011:

“Ever since plans to build a high-speed train from Las Vegas to Victorville, Calif., were unveiled, developers have been adamant about one point — they wouldn’t ask taxpayers to fund it.

But DesertXpress Enterprises has no qualms about borrowing from taxpayers — and borrowing big — for a project that skeptics say has little chance of gaining the ridership needed to pay for it.

The company has applied for a $4.9 billion loan through a federal program to construct what is billed as a $6 billion project. Since the plan was presented nearly two years ago, the cost estimate has ballooned from $4 billion.

The Federal Railroad Administration will hire an independent analyst to determine if ridership estimates, $50 one-way fares and other related revenue will be enough to repay the loan and prevent taxpayers from getting stuck with the bill.

The company, which is waiting for environmental clearances before it can begin preliminary design and engineering on the 185-mile route, requested the loan through the federal Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing program.

Under the program, funding may be used to develop or establish new railroad facilities, and direct loans can finance up to 100 percent of a railroad project with repayment periods of up to 35 years and interest rates the same as what the government is charged.

If approved, the loan would be more than four times the amount the program has lent to 28 railroad projects since 2002.

Since then, it has loaned $1.02 billion with the largest loan, $233 million, going to the Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern Railroad in 2003.”

……

“Developers chose Victorville because most passenger traffic in cars pass through the high-desert community en route to Las Vegas on I-15.

After critics ripped the Victorville end point, the company announced plans to build an extension west to Palmdale, where a station for the California high-speed rail project is planned.

The project also has been criticized because Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., a longtime supporter of a magnetic levitation system between Las Vegas and Los Angeles, withdrew his support and began backing DesertXpress in 2009. Reid said he was frustrated by the lack of progress on the maglev project, but critics said the switch was because DesertXpress investor Sig Rogich formed a campaign support group for Reid’s re-election months before the change in support.

DesertXpress officials have said a maglev is too expensive, but boosters of the technology say long-term costs are about the same because of the higher maintenance expense for traditional rail compared with the frictionless maglev, which is propelled on a magnetic field.”

Again Mr. Velotta writes on March 26, 2012 in the Desert Sun:

“I want to know if Sen. Harry Reid is getting frustrated with your lack of progress the way he did with the backers of a proposed maglev project.

You know the one I mean — the project that would have gone all the way to Los Angeles and Anaheim and better served Nevadans wanting to go to Southern California as well as Californians looking to come to Las Vegas.

The one with the technology capable of scaling Cajon Pass, unlike your technology.

The one embraced by several communities that viewed the line as a high-speed link between airports that could be used by commuters catching planes.

The senator pulled the financial rug from under the maglev project. Sure, he said he was frustrated that nothing had been accomplished in 30 years of maglev planning. But once the federal government passed legislation in 2008 to finance the engineering for a demonstration project, the senator managed to hijack that $45 million to other transportation projects a year later.”

…..

“I also want to know, DesertXpress, if you’re still confident in the Las Vegas-Victorville transportation model after all the scorn you’ve endured in the past four years. Aren’t you tired of hearing people say, “Victorville?” in disbelief when you explain that you’re asking Southern Californians to drive there, park their cars and board a train to take them on what would be the easier leg of the journey to Las Vegas? Let’s not forget, either, that our California visitors would have no car once they arrived in Nevada and would have to rely on public transportation, taxis or a rental. Never mind that there’s virtually no upside to Las Vegans looking to go to Southern California, either.

I’d like to know if you’ve rethought the maglev technology since the commercially operating line in Shanghai is maintaining a more than 99 percent on-time efficiency rating after eight years in service. Isn’t it about time we stop calling maglev “unproven?”

I know, your suppliers are all friends and steel-wheel-on-rail guys, the same ones who dominate policy at the Federal Railroad Administration. There’s virtually no hope that this is going to change with that good ol’ boy network in place, despite President Barack Obama’s urging to get the fastest train in the world deployed in the United States. I don’t think he was talking about a 150 mph system that most don’t consider to be high-speed rail anymore.”

As Mr. Mr. Velotta so eloquently points out folks in Nevada have no need for the DesertXpress. Suppose they want to go to Disneyland. What do they do? Take the train from Las Vegas to Victorville than rent a car to journey the next 70 or so miles to Anaheim. I don’t think so. In essence the DesertXpress is a one way train to take folks from Los Angeles, Riverside, and orange counties to Las Vegas and back for $100 dollars each way.

In 1991 I was involved with the proposed Maglev line from Anaheim to Las Vegas. This was to be a cooperative venture between Transrapid (the German consortium pushing their Maglev technology), The California High Speed Rail Corporation, Bechtel to design, build and operated a Maglev lain from Disneyland to Las Vegas. The technology seemed sound but there were two major problems. One is that they could not get a permit from Caltrans to use any right of way along the I-15 corridor and two; they could not find any investors. Eventually the right of way issue was solved by an act of the California Legislature, but there still was no money coming forth.

At the time there were no revenue generating Maglev lines anywhere in the world, not even in Germany. There were many nations interested, but no one wanted to pony up any bucks. Eventually, in January 2001, the Chinese signed an agreement with the German maglev consortium Transrapid to build an EMS high-speed maglev line to link Pudong International Airport with Longyang Road Metro station on the eastern edge of Shanghai. This Shanghai Maglev Train demonstration line, or Initial Operating Segment (IOS), has been in commercial operations since April 2004 and now operates 115 (up from 110 daily trips in 2010) daily trips that traverse the 19 miles between the two stations in just 7 minutes, achieving a top speed of 431 km/h (268 mph), averaging 266 km/h (165 mph). On a 12 November 2003 system commissioning test run, the Shanghai maglev achieved a speed of 501 km/h (311 mph), which is its designed top cruising speed for longer intercity routes. Unlike the old Birmingham maglev technology, the Shanghai maglev is extremely fast and comes with on time – to the second – reliability of greater than 99.97% The cost of this 19 mile line was 1.3 billion dollars — all paid by the Chinese government or about 68.4 million per mile. The line is totally subsidized by the Chinese government. The Birmingham line was closed before it ever opened.

In 1990, while working with the German Federal Railway (Deutsche

Klaus was right. The Transrapid/Bechtel Anaheim to Las Vegas maglev died a quick death and Bechtel lost several million dollars before pulling out of the venture. It was not until the Chinese decided to build an EMS line to show off for the 2004 Sumer Olympics and the benefits of their socialist state that any semblance of a revenue generating maglev line was constructed.

Now a private concern wants to build a steel-wheel train from Victorville to Las Vegas with a loan from the taxpayers. On May 10, 2012 Ainsley Earhardt of Fox News gave a good report on the status and hurdles facing DesertXpress Enterprises and the Victorville to Las Vegas train. (Click here to see her report)

While the city fathers in Victorville would like to see business generated in their high desert city the DesertXpress is not the way to go, To this day they have not been able to make the Southern California Logistic Airport (the old George AFB) a success. The only way this rail scheme can be built is for the federal government to pony up the taxpayer money. There is nothing in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution allowing them to do so. Why should a taxpayer in Montana or Arkansas be on the hook for 5 billion dollars for something they will never use nor achieve any benefit from? To me this is just another Solyndra project that the masterminds in Washington and Nevada want. If it’s that great why don’t the big hotel-casinos in Vegas pony up the bucks? I doubt that businessmen like Steve Wynn will make such an investment if he cannot see a good return.

No comments:

Post a Comment