"When we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them. But when we deal with the Japanese, we are on an entirely different field." — California Attorney General Earl Warren and latter Governor and Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

The following is an excerpt from an article I have published on my web site. You can access a full printable PDF version of the article by clicking here or an HTML version by clicking here.

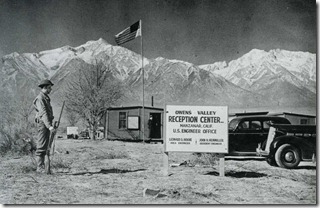

The most abhorrent act since the end of slavery in the United States was the relocation of thousands of Japanese-Americans to War Relocation Centers during the Second World War. These relocation centers were located in California, Arizona, Arkansas, Utah, Colorado, Idaho and Wyoming with one of the largest and most well-known was the center at Manzanar in the Owens Valley of California.

Approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese who lived along

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt authorized the internment with Executive Order 9066, issued February 19, 1942, which allowed local military commanders to designate "military areas" as "exclusion zones," from which "any or all persons may be excluded." This power was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the entire Pacific coast, including all of California and most of Oregon and Washington, except for those in internment camps. In 1944, the Supreme Court (Korematsu v. United States) upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, while noting that the provisions that singled out people of Japanese ancestry were a separate issue outside the scope of the proceedings. The United States Census Bureau assisted the internment efforts by providing confidential neighborhood information on Japanese Americans. The Bureau's role was denied for decades but was finally proven in 2007.

In 1905, John Shepherd sold his 1,300-acre George's Creek ranch to Charles Chaffey, brother of Southern California irrigation developer George Chaffey, for $25,000. The Chaffeys planned to turn Shepherd's and other properties nearby into an apple-growing subdivision modeled after the irrigated citrus colonies George had launched east of Los Angeles. Doing business as the Owens Valley Improvement Company, the Chaffeys and their investors called their venture the Manzanar Irrigated Farms. A town built in the center would be Manzanar, Spanish for "apple orchard."

Manzanar's orchards fell into neglect after 1934, but many kept producing, and each fall, local residents harvested their fruit for pies and preserves.

The Manzanar Relocation Center, established as the Owens Valley Reception Center, was first run by the U.S. Army's Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA). It later became the first relocation center to be operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The center was located at the former farm and orchard community of Manzanar. Founded in 1910, the

U.S. Department of Justice officials, meanwhile, had rounded up hundreds of Japanese aliens with ties to Japanese cultural or political activities. Families left behind faced growing isolation and uncertainty about their own futures

Japanese Americans were by far the most widely affected group, as all persons with Japanese ancestry were removed from the West Coast and southern Arizona. As then California Attorney General Earl Warren put it, "When we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them. But when we deal with the Japanese, we are on an entirely different field." In Hawaii, where there were 140,000 Americans of Japanese Ancestry (constituting 37% of the population), only selected individuals of heightened perceived risk were interned.

Americans of Italian and German ancestry were also targeted by these restrictions, including internment. 11,000 people of German ancestry were interned, as were 3,000 people of Italian ancestry, along with some Jewish

Many notable liberal progressives such as Roosevelt, William Douglas, Chief Justice Hugo Black and Earl Warren supported the internment of these Japanese Americans as vital to the war effort. One dissenting voice was that of J. Edgar Hoover the director of the FBI. Hoover’s opposition stemmed not so much from a constitutional or civil rights position, but from a belief that the FBI could handle any security threat to the United States from citizens of foreign ancestry. He believed that the most likely spies had already been arrested by the FBI shortly after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

It should be noted that not one case of espionage or treason was attributed to people of Japanese ancestry and the only real cases of treason or espionage were against Germans and Communists like Klaus Fuchs, Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs.

Executive Order No. 9066 came about as a result of great prejudice and

The order to have all Japanese-Americans relocated had serious consequences for the Japanese-American community. Even children adopted by Caucasian parents were removed from their homes to be relocated. Sadly, most of those relocated were American citizens by birth. Many families wound up spending three years in facilities. Most lost or had to sell their homes at a great loss and close down numerous businesses. This was a boon for the banks and real estate speculators.

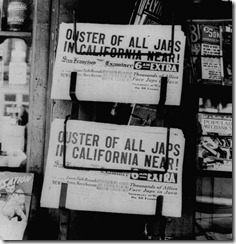

After the attack on Pearl Harbor many Caucasian Americans, who viewed the Japanese as competition, saw the Exclusionary Act as an opportunity get rid of their competition. “Japs not wanted” signs and posters were in abundance all along the west coast.

Thirty-six drab and depressingly identical barracks blocks, each with 300 or more occupants, functioned as both living and administrative units at

Special groups had their own living areas. Children of even partial Japanese heritage without parents or families-those in orphanages and foster care included-came under the mandatory evacuation order. All were brought to Manzanar, and a total of 101 children, together with staff, lived in the landscaped three-building Children's Village set in a firebreak near the pear orchard. Nearby, doctors and nurses had quarters at the hospital; other

More essential than the luggage Japanese Americans carried into Manzanar was their response to sudden confinement: "shikata ga ni," or "it cannot be helped." Most chose to go on with life: they fell in love, succeeded in school, worked productively, had fun, and learned new skills. "The threads of normal life that were broken with the evacuation were slowly mending," wrote the Manzanar Free Press. To people accustomed to work and activity, the enforced idleness and boredom of early camp life were, for many, more difficult to bear than the primitive barracks and inedible food. It was no surprise, then, that from the beginning, internees took the camp's urgent needs into their own hands when they could, and those with skills and talents stepped forward to help make the best of a very bad situation. Volunteer teachers started nursery schools, gardeners planted lawns, restaurant chefs helped set up mess halls, and doctors and nurses organized a hospital.

Leisure-time activities gave morale a lift as well, and a WRA Community Activities section employed 150 internees who supervised arts and crafts, athletics, gardening, music, the Boy Scouts, and social events. Weekly

The decades-long effort to gain recognition for Manzanar led to designations as a California State Landmark, a National Historic Landmark, and, in 1992, a National Historic Site. Today a new, nonresident community includes National Park Service staff and nearly 90,000 visitors annually. Among them are many who once lived at Manzanar.

It was not until 1988 when President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government. The legislation stated that government actions were based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership", and beginning in 1990, the government paid $20,000 in reparations to the surviving internees.

We must remember the words of Benjamin Franklin when he said; “They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.

This post is an excerpt from a longer and more detailed article about Manzanar I have published on the Web. You can read the full PDF version of the article by clicking here or an HTML version by clicking here.

You can access a full gallery of photos from my visit to Manzanar by clicking here

No comments:

Post a Comment