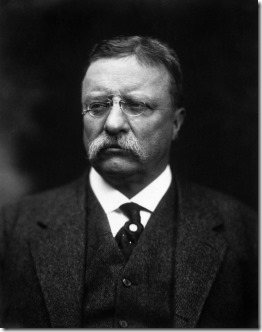

“No matter how honest and decent we are in our private lives, if we do not have the right kind of law and the right kind of administration of the law, we cannot go forward as a nation.” — Theodore Roosevelt, August 31, 1910

The Progressive movement in America spanned the period between the dawn of the 20th century and the 1930s. Animated by a common dedication to statism, and influenced by the ideas of Darwin, self-identified Progressives believed that the problems associated with the urban and industrial revolutions required government to assume a more active and powerful role in the lives of citizens.

After the expansion of our industrial economy during the Gilded Age and the growth of our cities due to the migrations of Europeans from 1980 to the beginning of World War One Progressives believed that our form of constitutional government as laid down by our Founding Fathers was no longer adequate for the governance of the nation. They began to believe more and more in a government less focused on self-government and more on the administrative state where university educated masterminds were more capable to govern the masses than the people through their elected representatives.

Animated by historicism and relativism, which dominated the intellectual climate in the 19th century, Progressives argued that because truths are contingent on a specific time and context-rather than permanent and enduring for all people and all ages-the principles and institutions of government must change and evolve over time in tandem with social and scientific changes.

Woodrow Wilson echoed these sentiments, declaring "All that Progressives ask or desire

Progressives argued that for a truly just and democratic government, the business of politics-namely, elections-should be separated from the administration of government, which would be overseen by nonpartisan, and therefore, neutral, experts. The president, as the only nationally elected public official, best embodies the will of the people, resulting in a legislative mandate to create administrative agencies and government aid programs to improve the lives of citizens.

This is what we have been living under for the past 100 years and it has culminated with Barak Obama, his czars, and his regulations. The legislature is becoming less and less a factor in governance with the executive, with the assistance of the courts, becoming more and powerful. The term for this is “administrative statism.”

The pillars Progressivism are:

- Historicism,

- A Living Constitution,

- Legal Positivism,

- Administration, and

- Federal Police Power.

Historicism is the term used to describe historical contingency or the belief that there is no permanent truth. The early progressives, such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, rejected the Founder’s idea of Natural Rights as expressed in the Declaration of Independence They believed that even the Constitution with its separation and balance of powers was authored by men who were dedicated the Newtonian science and the philosophies of men like Locke and Montesquieu. They further believed that since the industrial revolution and the growth of urban development rights had to be redefined based upon Darwinian thinking and experts in government. In essence that believed in an evolving truth based on the contingencies of history.

He was severely disappointed in the conservative administration of his successor and friend, William Howard Taft, and challenged him for the Republican nomination in 1912. His campaign for a “New Nationalism” marked a dramatic leap ahead in his belief in the power of the national government’s role in the nation’s political economy.

On August 31, 1910 he gave a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas (the same city selected by Barack Obama to give his “fairness” and wealth distribution speech in 2012) where he outlined his policies for his New Nationalism. In the speech Roosevelt stated:

“I stand for the square deal. But when I say that I am for the square deal, I mean not merely that I stand for fair play under the present rules of the game, but that I stand for having those rules changed so as to work for a more substantial equality of opportunity and of reward for equally good service. One word of warning, which, I think, is hardly necessary in Kansas. When I say I want a square deal for the poor man, I do not mean that I want a square deal for the man who remains poor because he has not got the energy to work for himself. If a man who has had a chance will not make good, then he has got to quit.

…

In every wise struggle for human betterment one of the main objects, and often the only object, has been to achieve in large measure equality of opportunity. In the struggle for this great end, nations rise from barbarism to civilization, and through it people press forward from one stage of enlightenment to the next. One of the chief factors in progress is the destruction of special privilege. The essence of any struggle for healthy liberty has always been, and must always be, to take from some one man or class of men the right to enjoy power, or wealth, or position, or immunity, which has not been earned by service to his or their fellows. That is what you fought for in the Civil War, and that is what we strive for now.

…

The object of government is the welfare of the people. The material progress and prosperity of a nation are desirable chiefly so long as they lead to the moral and material welfare of all good citizens. Just in proportion as the average man and woman are honest, capable of sound judgment and high ideals, active in public affairs,-but, first of all, sound in their home, and the father and mother of healthy children whom they bring up well,-just so far, and no farther, we may count our civilization a success. We must have-I believe we have already-a genuine and permanent moral awakening, without which no wisdom of legislation or administration really means anything; and, on the other hand, we must try to secure the social and economic legislation without which any improvement due to purely moral agitation is necessarily evanescent. Let me again illustrate by a reference to the Grand Army. You could not have won simply as a disorderly and disorganized mob. You needed generals; you needed careful administration of the most advanced type; and a good commissary-the cracker line. You well remember that success was necessary in many different lines in order to bring about general success. You had to have the administration at Washington good, just as you had to have the administration in the field; and you had to have the work of the generals good. You could not have triumphed without the administration and leadership; but it would all have been worthless if the average soldier had not had the right stuff in him. He had to have the right stuff in him, or you could not get it out of him. In the last analysis, therefore, vitally necessary though it was to have the right kind of organization and the right kind of generalship, it was even more vitally necessary that the average soldier should have the fighting edge, the right character. So it is in our civil life. No matter how honest and decent we are in our private lives, if we do not have the right kind of law and the right kind of administration of the law, we cannot go forward as a nation. That is imperative; but it must be an addition to, and not a substitute for, the qualities that make us good citizens. In the last analysis, the most important elements in any man’s career must be the sum of those qualities which, in the aggregate, we speak of as character. If he has not got it, then no law that the wit of man can devise, no administration of the law by the boldest and strongest executive, will avail to help him. We must have the right kind of character-character that makes a man, first of all, a good man in the home, a good father, and a good husband-that makes a man a good neighbor. You must have that, and, then, in addition, you must have the kind of law and the kind of administration of the law which will give to those qualities in the private citizen the best possible chance for development. The prime problem of our nation is to get the right type of good citizenship and, to get it, we must have progress, and our public men must be genuinely progressive.” (Emphasis added)

As you can see Teddy Roosevelt was proclaiming a remarkable departure from our Founders who proclaimed:

“..all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

As you can see Roosevelt believed in an “equality of opportunity” and that it was government’s role to provide those opportunities. This speech was precursor to Obama’s 2012 speech I the same town where he stated it government’s role to provide “fairness” and that wealth should be redistributed in a fairer mode through the tax code.

In 1887 Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act. The act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just," but did not empower the government to fix specific rates. It also required that railroads publicize shipping rates and prohibited short haul or long haul fare discrimination, a form of price discrimination against smaller markets, particularly farmers. The Act created a federal regulatory agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which it charged with monitoring railroads to ensure that they complied with the new regulations.

The Act was the first federal law to regulate private industry in the United States. It was later amended to regulate other modes of transportation and commerce. This was only the first of many moves by Progressives to begin regulating the economy and business.

During the 1902 anthracite coal strike, a strike that lasted 163 days, caused by a dispute between the union and the mine owners Teddy Roosevelt intervened and wanted the Army to take over the coal mines. He was told by his Attorney General, Philander Knox, that he had no authority to do so. Mark Hanna and many others in the Republican Party were likewise concerned about the political implications if the strike dragged on into winter, when the need for anthracite was greatest. As Roosevelt told Hanna, "A coal famine in the winter is an ugly thing and I fear we shall see terrible suffering and grave disaster.

To this effect Roosevelt therefore convened a conference of representatives of government, labor, and management on October 3, 1902. The union considered the mere holding of a meeting to be tantamount to union recognition and took a conciliatory tone. The owners told Roosevelt that strikers had killed over 20 men and that he should use the power of government "to protect the man who wants to work, and his wife and children when at work." With proper protection they would produce enough coal to end the fuel shortage; they refused to enter into any negotiations with the union. The governor sent in the National Guard, who protected the mines and the minority of men still working. Roosevelt attempted to persuade the union to end the strike with a promise that he would create a commission to study the causes of the strike and propose a solution, which Roosevelt promised to support with all of the authority of his office. This was the first time since the Civil War that the federal government became involved in labor dispute.

This strike was successfully mediated through the intervention of the federal government, which strove to provide a "Square Deal"—which Roosevelt took as the motto for his administration—to both sides. The settlement was an important step in the Progressive era reforms of the decade that followed. There were no more major coal strikes until the 1920s. In essence Roosevelt said the hell with the Constitution, people need coal. Now it became the role of the federal government to involve itself in labor disputes. This would be the forerunner of the creation of the National Labor Relations Board.

The presidential election of 1912 pitted the incumbent Howard Taft against the Democratic Party nominee Woodrow Wilson. Teddy Roosevelt who was unhappy with four years of the Taft administration entered the race as a third party candidate for the Progressive Party. The election was won by Wilson with 42% of the vote. Roosevelt’s square deal Progressive Party received 27% and the more conservative Republican Taft 23% — thus entered a new dawn for Progressivism in the United States.

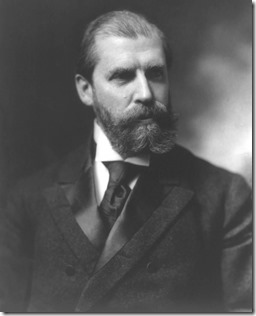

Wilson began his graduate studies at the German-minded Johns Hopkins University in 1883 and three years later completed his doctoral dissertation, "Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics" and received a Ph.D. in history and political science.

Wilson was a fan of the British parliamentary form of government and had disdain for Congress, especially the House of Representatives, and our system of checks and balances for which he stated:

”.. divided up, as it were, into forty-seven seignories, in each of which a Standing Committee is the court-baron and its chairman lord-proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within reach [of] the full powers of rule, may at will exercise an almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself.” (definition added)

Wilson said that the Congressional committee system was fundamentally undemocratic in that committee chairs, who ruled by seniority, determined national policy although they were responsible to no one except their constituents; and that it facilitated corruption.

When William Jennings Bryan captured the Democratic nomination from Cleveland's supporters in 1896, Wilson refused to support the ticket. Instead, he cast his ballot for John M. Palmer, the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party, or Gold Democrats, a short-lived party that supported a gold standard, low tariffs, and limited government.

In his last scholarly work in 1908, Constitutional Government of the United States, Wilson said that the presidency "will be as big as and as influential as the man who occupies it". By the time of his presidency, Wilson hoped that Presidents could be party leaders in the same way British prime ministers were. Wilson also hoped that the parties could be reorganized along ideological, not geographic, lines. He wrote, "Eight words contain the sum of the present degradation of our political parties: “No leaders, no principles; no principles, no parties.”

Historians have struggled to give a clear definition to the progressive movement. In general, it was a mood among middle-class professionals that order needed to be imposed on the chaotic American free enterprise system. Progressives addressed most of the same concerns as the Populists, but did so from a broader base, in a less angry, alienated, and apocalyptic way, for many progressives were themselves the products of the economic system that they sought to reform. Thus, the progressive movement was thoroughly ambivalent, and progressives frequently took opposite sides on many issues, and produced contradictory legislation, and often faced unintended consequences. But the one unifying theme of progressivism was statism: At one level or another, progressives called for increased governmental power to deal with social problems. It was in this period that the term “liberal” was inverted from its nineteenth century laissez-faire to its twentieth century big-government definition.

Progressives usually favored the expansion of executive power, seeing nineteenth-century politics dominated by legislatures and courts, and above all by corrupt parties in cahoots with business interests. Woodrow Wilson, an academic political scientist before entering politics, was a pivotal progressive theorist. Wilson was the first prominent thinker to argue that the founders’ constitutional system had become obsolete and needed to be radically altered. Reflecting the evolutionary ethos of the era, Wilson argued that a constitution was an organism that must grow and adapt, or die. Federalism, separation of powers, checks-and-balances—the various devices by which the Constitution limited government power—now rendered the government incapable of dealing with contemporary problems. Furthermore he believed that a state should be governed by expert administrators and that academia should be considered the fourth branch of government. In 1913 he wrote in his book “The New Freedoms”, which was a compendium of his 1912 campaign speeches. In his chapter titled “The Old Order Changeth” Wilson stated:

“We are in the presence of a new organization of society. Our life has broken away from the past. The life of America is not the life that it was twenty years ago; it is not the life that it was ten years ago. We have changed our economic conditions, absolutely, from top to bottom; and, with our economic society, the organization of our life. The old political formulas do not fit the present problems; they read now like documents taken out of a forgotten age. The older cries sound as if they belonged to a past age which men have almost forgotten. Things which used to be put into the party platforms of ten years ago would sound antiquated if put into a platform now. We are facing the necessity of fitting a new social organization, as we did once fit the old organization, to the happiness and prosperity of the great body of citizens; for we are conscious that the new order of society has not been made to fit and provide the convenience or prosperity of the average man. The life of the nation has grown infinitely varied. It does not center now upon questions of governmental structure or of the distribution of governmental powers. It centres upon questions of the very structure and operation of society itself, of which government is only the instrument. Our development has run so fast and so far along the lines sketched in the earlier day of constitutional definition, has so crossed and interlaced those lines, has piled upon them such novel structures of trust and combination, has elaborated within them a life so manifold, so full of forces which transcend the boundaries of the country itself and fill the eyes of the world, that a new nation seems to have been created which the old formulas do not fit or afford a vital interpretation of. We have come upon a very different age from any that preceded us. We have come upon an age when we do not do business in the way in which we used to do business,-when we do not carry on any of the operations of manufacture, sale, transportation, or communication as men used to carry them on. There is a sense in which in our day the individual has been submerged. In most parts of our country men work, not for themselves, not as partners in the old way in which they used to work, but generally as employees,-in a higher or lower grade,-of great corporations. There was a time when corporations played a very minor part in our business affairs, but now they play the chief part, and most men are the servants of corporations.”

Wilson's position in 1912 stood in opposition to Progressive party candidate Theodore Roosevelt's ideas of New Nationalism, particularly on the issue of antitrust modification. According to Wilson, "If America is not to have free enterprise, he can have freedom of no sort whatever." In presenting his policy, Wilson warned that New Nationalism represented collectivism, while New Freedom stood for political and economic liberty from such things as trusts. Wilson was strongly influenced by his chief economic advisor Louis D. Brandeis, an enemy of big business and monopoly.

Although Wilson and Roosevelt agreed that economic power was being abused by trusts, Wilson ideas split with Roosevelt on how the government should handle the restraint of private power as in dismantling corporations that had too much economic power in a large society.

However, once elected, Wilson seemed to abandon his "New Freedom" and adopted policies that were more similar to those of Roosevelt's New Nationalism, such as the Federal Reserve System. Wilson appointed Brandeis to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1916. He worked with Congress to give federal employees worker's compensation, outlawed child labor with the Keating-Owen Act (though this act was ruled unconstitutional in 1918) and passed the Adamson Act, which secured a maximum eight-hour workday for railroad employees. Most important was the Clayton Act of 1914, which largely put the trust issue to rest by spelling out the specific unfair practices that business were not allowed to engage in.

Wilson proved especially effective in mobilizing public opinion behind tariff changes by denouncing corporate lobbyists, addressing Congress in person in highly dramatic fashion, and staging an elaborate ceremony when he signed the bill into law. The revenue lost by a lower tariff was replaced by a new federal income tax, authorized by the 16th Amendment. Wilson managed to bring all sides together on the issues of money and banking by the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System, a complex business-government partnership that to this day dominates the financial world

By the end of the Wilson Administration, a significant amount of progressive legislation had been passed, affecting not only economic and constitutional affairs, but farmers, labor, veterans, the environment, and conservation as well. The reform agenda of the New Freedom, however, did not extend as far as Theodore Roosevelt's proposed New Nationalism in relation to the latter's calls for a standard 40-hour work week, minimum wage laws, and a federal system of social insurance. This was arguably a reflection of Wilson's own ideological convictions, which adhered to the classical liberal principles of Jeffersonian Democracy (although Wilson did champion reforms such as agricultural credits later in his presidency and called for a living wage in his last State of the Union Address). Despite this, the New Freedom did much to extend the power of the federal government in social and economic affairs, and arguably paved the way for future reform programs such as the New Deal and the Great Society.

One thing Progressive love is chaos or war as these provide the impetus and reasons to give the federal government more power. While Wilson did not advance his progressive agenda that much during his first term he certainly made up for it in his second.

The election of 1916 was very close. Wilson’s popularity was never that high and he had not lived up to his progressive agenda. He was challenged by Charles Evans Hughes. After

WWI gave Wilson the opportunity to push many of Progressive and in some cases tyrannical laws though Congress and with the passage of the 16th Amendment (income tax) he was able to raise the this tax to 75% and it was not reduced to 25% until the Coolidge Administration.

To counter opposition to the war at home, Wilson pushed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war opinions. While he welcomed socialists who supported the war, he pushed at the same time to arrest and deport foreign-born radicals. Citing the Espionage Act, the U.S. Post Office, following the instructions of the Justice Department, refused to carry any written materials that could be deemed critical of the U.S. war effort. Some sixty newspapers judged to have revolutionary or antiwar content were deprived of their second-class mailing rights and effectively banned from the U.S. mails. Mere criticism of the Wilson administration and its war policy became grounds for arrest and imprisonment. A Jewish immigrant from Germany, Robert Goldstein, was sentenced to ten years in prison for producing The Spirit of '76, a film that portrayed the British, now an ally, in an unfavorable light.

Wilson's domestic economic policies were strongly pro-labor, but this favorable treatment was extended to only those unions that supported the U.S. war effort, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Antiwar groups, anarchists, communists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other radical labor movements were regularly targeted by agents of the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested on grounds of incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition. By 1918, the ranks of those arrested included Eugene Debs, the mild-mannered Socialist Party leader and labor activist, after he gave a speech opposing the war. Debs' opposition to the Wilson administration and the war earned the undying enmity of President Wilson, who later called Debs a "traitor to his country". Many recent foreign immigrants, resident aliens who opposed America's participation in World War I, were eventually deported to Soviet Russia or other nations under the sweeping powers granted in the Immigration Act of 1918, which had actually been drafted by Wilson administration officials at the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Immigration. Even after the war ended in November 1918, the Wilson administration's attempts to silence radical political opponents continued, culminating in the Palmer Raids, a mass arrest and roundup of some

In October 1917, President Wilson and Congress created the Office of the Alien Property Custodian; and Palmer, prior to being appointed Attorney General, was appointed by Wilson to head this agency. On July 15, 1918, President Wilson gave Palmer the power to sell enemy-owned property worth less than $10,000 privately without public auction. Palmer's sale manager, Joseph Guffy, was later indicted on 12 counts for embezzlement of the sale funds, although Guffy was never brought to trial. In the Philippines, transactions of German property sales were rigged for sale to private friends of the local manager. Although Palmer revoked the sales under President Wilson's support, he appointed a new agent who then resold the properties to the original purchasers. In December 1918, Palmer was under suspicion that the sale of Bosch Magneto Company had been rigged, when the firm was sold to Palmer's friend who owned a truck manufacturing business. Palmer also was criticized in 1920 for having sold 5,000 German chemical patents too cheaply.

Wilson set up the first western propaganda office, the United States Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel (thus its popular name, Creel Commission), which filled the country with patriotic anti-German appeals and conducted various forms of censorship. In 1917, Congress authorized ex-President Theodore Roosevelt to raise four divisions of volunteers to fight in France — Roosevelt's World War I volunteers; Wilson refused to accept this offer from his political enemy. Other areas of the war effort were incorporated into the government along with propaganda. The War Industries Board headed by Bernard Baruch set war goals and policies for American factories. Future President Herbert Hoover was appointed to head the Food Administration which encouraged Americans to participate in "Meatless Mondays" and "Wheatless Wednesdays" to conserve food for the troops overseas. The Federal Fuel Administration run by Henry Garfield introduced daylight savings time and rationed fuel supplies such as coal and oil to keep the U.S. military supplied. These and many other boards and administrations were headed by businessmen recruited by Wilson for a-dollar-a-day salary to make the government more efficient in the war effort. Wilson also segregated the army and the federal government and could be considered the most racist president since the Civil War.

By the end of WWI in 1918 the Wilson had trampled on Article I of the Constitution and the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments of the Constitution with little or no opposition from the courts or Congress. This is what progressivism had wrought in a mere two years.

In my next post on this subject I will continue with the years from 1920 to the beginning of the Second World War to show how there was a brief period of retreat from the onward march of progressivism from 1920 to 1928, but this rise of big statist government began once again with the 1929 stock market crash and the administrations of Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt.

No comments:

Post a Comment