“If we are bold in our thinking, courageous in accepting new ideas, and willing to work with instead of against our land, we shall find in conservation farming an avenue to the greatest food production the world has ever known — not only for the war, but for the peace that is to follow.” — Hugh Hammond Bennett, 1943.

Palm Sunday, April 14, 1935, dawned clear across the plains. After weeks of dust storms, one near the end of March destroying five million acres of wheat, people grateful to see the sun went outside to do chores, go to church, or to picnic and sun themselves under the blue skies. In mid-afternoon, the temperature dropped and birds began chattering nervously. Suddenly, a huge black cloud rising to over 10,000 feet appeared on the horizon, approaching fast.

Those on the road had to try to beat the storm home. Some, like Ed and Ada Phillips of Boise City, and their six-year-old daughter, had to stop on their way to seek shelter in an abandoned adobe hut. There they joined ten other people already huddled in the two-room ruin, sitting for four hours in the dark, fearing that they would be smothered. Cattle dealer Raymond Ellsaesser tells how he almost lost his wife when her car was shorted out by electricity and she decided to walk the three-quarters of a mile home. As her daughter ran ahead to get help, Ellsaesser’s wife wandered off the road in the blinding dust. The moving headlights of her husband’s truck, visible as he frantically drove back and forth along the road, eventually led her back.

The drought hit first in the eastern part of the country in 1930. In 1931, it moved toward the west. By 1934 it had turned the Great Plains into a desert. “If you would like to have your heart broken, just come out here,” wrote Ernie Pyle, a roving reporter in Kansas, just north of the Oklahoma border, in June of 1936. “This is the dust-storm country. It is the saddest land I have ever seen.”

The Dust Bowl got its name on April 15, 1935, the day after “Black Sunday.”

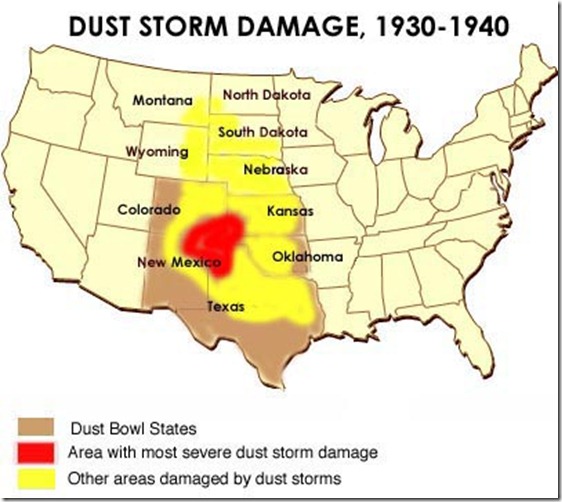

The Soil Conservation Service used the term on their maps to describe “the western third of Kansas, Southeastern Colorado, the Oklahoma Panhandle, the northern two-thirds of the Texas Panhandle, and northeastern New Mexico.” The SCS Dust Bowl region included some surrounding area, to cover one-third of the Great Plains, close to 100 million acres, 500 miles by 300 miles. It is thought that Geiger was referring to an earlier image of the plains coined by William Gilpin, who had compared the Great Plains to a fertile bowl, rimmed by mountains. Residents hated the label, which was thought to play a part in diminishing property values and business prospects in the region.

Within a week the black dust from the storm had passed over Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York City, and Washington D.C. It was reported that ships in the Atlantic Ocean as far as 300 miles off the coast reported the black dust falling on their decks. The dust fell on the Capital Building and the White House and President Roosevelt reported that he could run his finger across his desk in the Oval Office and trace a line through the dust.

The storm on Black Sunday was the last major dust storm of the year, and the damage it caused was not calculated for months. Coming on the heels of a stormy season, the April 14 storm hit as many others had, only harder. “The impact is like a shovelful of fine sand flung against the face,” Avis D. Carlson wrote in a New Republic article:

“People caught in their own yards grope for the doorstep. Cars come to a standstill, for no light in the world can penetrate that swirling murk. The nightmare is deepest during the storms. But on the occasional bright day and the usual gray day we cannot shake from it. We live with the dust, eat it, sleep with it, watch it strip us of possessions and the hope of possessions. It is becoming real. The poetic uplift of spring fades into a phantom of the storied past. The nightmare is becoming life.”

In the 1910s and 1920s the southern Plains was "the last frontier of agriculture" according to the government, when rising wheat prices, a war in Europe, a series of unusually wet years, and generous federal farm policies created a land boom — the Great Plow-Up that turned 5.2 million acres of thick native grassland into wheat fields. Newcomers rushed in and towns sprang up overnight

The American wheat farmer rode an economic roller coaster from the beginning of World War I to the start of the Second World War. Wholesale prices climbed sharply even before the United States entered World War I and peaked shortly after its end.

The resumption of European farm production flooded world markets in the Twenties, guaranteeing years of low prices. American agriculture was clearly mired in deep depression long before the stock market crash of 1929. By the early 1930s, many farmers were receiving less for their crop than its cost of production — a certain recipe for default and foreclosure

According the USDA 1889-1919 was a Period of farm prosperity. In 1919, after the end of the First World War wheat had skyrocketed to an all-time high of $2.16 per bushel ($28.88 adjusted per the CPI to 2012). This boom in wheat prices caused farmers to rip up more and more acres of the native grasslands, grasslands that had held the soil in place for hundreds of years, and plant wheat. They were using giant tractors pulling up to ten racks of disks ripping the soil in straight lines to make way for rows of wheat. These rows did not follow the contours of the land, but followed the ordinal directions of their section boundaries. It also encouraged so-called “suitcase farmers” to come from the east to buy up as much land as they could for growing wheat. This caused a rapid escalation in the price of the land. Everything was going great until 1929 and the great stock market crash.

As the nation sank into the Depression and wheat prices plummeted from $2.16 a bushel to 38 cents in 1932, farmers responded by tearing up even more prairie sod in hopes of harvesting bumper crops. When prices fell even further, the "suitcase farmers" who had moved in for quick profits simply abandoned their fields. Huge swaths of eight states, from the Dakotas to Texas and New Mexico, where native grasses had evolved over thousands of years to create a delicate equilibrium with the wild weather swings of the Plains, now lay naked and exposed.

In 1931 the rains stopped and the “black blizzards” began. Powerful dust storms carrying millions of tons of stinging, blinding black dirt swept across the Southern Plains—the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, western Kansas, and the eastern portions of Colorado and New Mexico. Topsoil that had taken a thousand years per inch to build suddenly blew away in only minutes.

In 1932, the weather bureau reported fourteen dust storms. The next year, the number climbed to thirty-eight. People tried to protect themselves by hanging wet sheets in front of doorways and windows to filter the dirt. They stuffed window frames with gummed tape and rags. But keeping the fine particles out was impossible. The dust permeated the tiniest cracks and crevices. Through it all, the farmers kept plowing, kept sowing wheat, kept waiting for rain.

By 1934, the storms were coming with alarming frequency. Residents believed they could determine a storm’s point of origin by the color of the dust — black from Kansas, red from Oklahoma, gray from Colorado or New Mexico.

The dust was beginning to make living things sick. Animals were found dead in the fields, their stomachs coated with two inches of dirt. People spat up clods of dirt as big around as a pencil. An epidemic raged throughout the Plains: they called it dust pneumonia.

By the end of 1935, with no substantial rainfall in four years, some residents gave up. Dust Bowlers watched as their neighbors and friends picked up and

In 1936, Dust Bowlers saw their first ray of hope: an innovative plan spearheaded by Hugh Bennett, a leading agricultural expert, to conserve valuable topsoil. He persuaded Congress to approve a federal program that would pay farmers to use new farming techniques. By 1937, the soil conservation campaign was in full swing. By the next year the soil loss had been reduced by sixty-five percent. Though the new techniques were taking root and the situation had improved, the drought dragged on. (See the timeline for the Dust Bowl by clicking here.)

In the early years of the 1930s, the extent of the damage inflicted on the southern plains by the drought and dust storms was little noticed outside of the region. The nation, led by the newly elected Franklin D. Roosevelt, was desperately trying to recover from the shock of the Great Depression. Most citizens were too worried about getting food on their plates to even think about the plight of farmers in the Great Plains. Certain members of Roosevelt’s administration, however, realized that the average American’s fate was closely tied to that of Dust Bowl farmers. One of these was Hugh Hammond Bennett, who would come to be known as “the father of soil conservation.”

Bennett had begun his campaign to preserve the soil by reforming farming practices before Roosevelt became president. He had joined the Department of Agriculture in the early 1900s. His mission to address the problems of land depletion was spurred on by the 1909 Bureau of Soils announcement, “The soil is the one indestructible, immutable asset that the nation possesses. It is the one resource that cannot be exhausted; that cannot be used up.” Throughout his career, Bennett worked to prove just how wrong this statement was.

In 1933 Bennett was made director of the newly formed Soil Erosion Service, which worked to combat erosion caused by dust storms by reforming farming methods. “Americans have been the greatest destroyers of land of any race or people, barbaric or civilized,” he announced, calling for “a tremendous national awakening to the need for action in bettering our agricultural practices.” Although his criticisms of Dust Bowl farming techniques raised the backs of farmers, he saw his reforms as necessary to avoid similar catastrophes in the future.

Bennett gained the support of Congress with the help of a providentially timed storm from the plains that hit Washington, D.C. in May 1934, while he was testifying before a congressional committee. Experiencing a debilitating dust storm for the first time in the Capital, Congress put its weight behind the Soil Conservation Act of 1935, which focused on improving farming techniques.

Bennett was a champion of soil conservation methods, such as crop rotation and replant native prairie grasses, contour plowing, and the planting of wind breaks, to the extent that he favored reverting a large part of the Great Plains back to grasslands. The federal government also bought more than 10 million acres and converted them to grasslands, some managed today by the U.S. Forest Service. He wrote in 1943, “If we are bold in our thinking, courageous in accepting new ideas, and willing to work with instead of against our land, we shall find in conservation farming an avenue to the greatest food production the world has ever known – not only for the war, but for the peace that is to follow.”

When the drought and dust storms showed no signs of letting up, many people abandoned their land. Others would have stayed but were forced out when they lost their land in bank foreclosures. In all, one-quarter of the population left, packing everything they owned into their cars and trucks, and headed west toward California. Although overall three out of four farmers stayed on their land, the mass exodus depleted the population drastically in certain areas. In the rural area outside Boise City, Oklahoma, the population dropped 40% with 1,642 small farmers and their families pulling up stakes.

The Dust Bowl exodus was the largest migration in American history. By 1940, 2.5 million people had moved out of the Plains states; of those, 200,000 moved to California. When they reached the border, they did not receive a warm welcome as described in this 1935 excerpt from Collier’s magazine:

“Very erect and primly severe, [a man] addressed the slumped driver of a rolling wreck that screamed from every hinge, bearing and coupling. 'California’s relief rolls are overcrowded now. No use to come farther,’ he cried. The half-collapsed driver ignored him — merely turned his head to be sure his numerous family was still with him. They were so tightly wedged in, that escape was impossible. 'There really is nothing for you here,’ the neat trooperish young man went on. 'Nothing, really nothing.’ And the forlorn man on the moaning car looked at him, dull, emotionless, incredibly weary, and said: 'So? Well, you ought to see what they got where I come from.’ “

The Los Angeles police chief went so far as to send 125 policemen to act as bouncers at the state border, turning away “undesirables”. The LAPD was operating under a vague law by asking if each family crossing over the Colorado River at Needles on Route 66 had $50.00. If they did not have that amount they were considered as “vagrants” and turned back. Called “the bum brigade” by the press and the object of a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union, the LAPD posse was recalled only when the use of city funds for this work was questioned.

John Steinbeck’s story of migrating tenant farmers in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1939 novel, “The Grapes of Wrath,” tends to obscure the fact that upwards of three-quarters of farmers in the Dust Bowl stayed put. Dust Bowl refugees did not flood California. Only 16,000 of the 1.2 million migrants to California during the 1930s came from the drought-stricken region. Most Dust Bowl refugees tended to move only to neighboring states.

Arriving in California, the migrants were faced with a life almost as difficult as the one they had left. Many California farms were corporate-owned. They were larger and more modernized that those of the southern plains, and the crops were unfamiliar. The rolling fields of wheat were replaced by crops of fruit, nuts and vegetables. Like the Joad family in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath”, some 40 percent of migrant farmers wound up in the San Joaquin Valley, picking grapes and cotton. They took up the work of Mexican migrant workers, 120,000 of whom were repatriated during the 1930s. Life for migrant workers was hard. They were paid by the quantity of fruit and cotton picked with earnings ranging from seventy-five cents to $1.25 a day. Out of that, they had to pay twenty-five cents a day to rent a tar-paper shack with no floor or plumbing. In larger ranches, they often had to buy

As roadside camps of poverty-stricken migrants proliferated, growers

When migrants reached California and found that most of the farmland was tied up in large corporate farms, many gave up farming. They set up residence near larger cities in shack towns called Little Oklahomas or Okievilles on open lots local landowners divided into tiny subplots and sold cheaply for $5 down and $3 in monthly installments. They built their houses from scavenged scraps, and they lived without plumbing and electricity. Polluted water and a lack of trash and waste facilities led to outbreaks of typhoid, malaria, smallpox and tuberculosis.

Over the years, they replaced their shacks with real houses, sending their children to local schools and becoming part of the communities; but they continued to face discrimination when looking for work, and they were called “Okies” and “Arkies” by the locals regardless of where they came from.

As a person who had driven across Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico (parts of the Dust Bowl) I was intrigued to watch the PBS series on the Dust Bowl last week. The Dust Bowl, a two-part, four-hour documentary series by Ken Burns, that aired on November 18 and 19, 2012, 8:00-10:00 p.m. on PBS The film chronicles the environmental catastrophe that, throughout the 1930s, destroyed the farmlands of the Great Plains, turned prairies into deserts, and unleashed a pattern of massive, deadly dust storms that for many seemed to herald the end of the world. It was the worst manmade ecological disaster in American history.

The film is also a story of heroic perseverance against enormous odds: families finding ways to survive and hold on to their land, New Deal programs that kept hungry families afloat, and a partnership between government agencies and farmers to develop new farming and conservation methods.

The Dust Bowl chronicles this critical moment in American history in all its complexities and profound human drama. It is part oral history, using compelling interviews of 26 survivors of those hard times — what will probably be the last recorded testimony of the generation that lived through the Dust Bowl. Filled with seldom seen movie footage, previously unpublished photographs, the songs of Woody Guthrie, and the observations of two remarkable women who left behind eloquent written accounts, the film is also a historical accounting of what happened and why during the 1930s on the southern Plains.

As a person who does not normally watch anything on PBS due to its progressive leaning agenda I thought the two part series was very well done and gave an accurate portrayal of the period from 1931 to 1947. There were times during the film when Burns drifted into his progressive agenda with his portrayal of Roosevelt and the New Deal. The one main criticism I did, however, have against the film was the repetitive use of photographs from the period and the sometimes too long interview segments. As David Wiegand states in his review of the film in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“But as a film, "Dust Bowl" is sadly lacking. It's in dire need of tighter editing, most of all. Yes, the images from the '30s are powerful, but after a while, their power is diminished by repetition. The script is informative, but it's also so full of itself, you're even more grateful when you get to listen to the people who were actually there, as opposed to the solemn tones of Coyote reading Duncan's bloviated, redundant prose. There's also a section of the film about how the Okies were treated in California. It's interesting for a few minutes, but very soon begins to feel beside the point and, again, in need of editing.

But this is how Ken Burns makes films. He has a template and rarely varies from it. When he gets carried away and isn't sufficiently detached to make needed cuts and to sharpen his focus, we get "The Dust Bowl" or "The National Parks: America's Best Idea," a six-part slog that made you want to fell every tree in Yellowstone.

"Dust Bowl" isn't quite that bad, not just because it's not as long, but because of the people who were there. Their simple words and detailed memories make this film necessary. Even all these years later, you can see and hear how fresh the memories remain, and it breaks your heart.”

I agree with Mr. Wiegand’s assessment of the film when he refers to the overly repetitive use of the vintage photos. This repetition, while interesting and informative, can cause a dulling of the senses and lose the effect of the photographs. With that said I still recommend the film to anyone interested in American History.

There is also a worthwhile article on History.com that explores the ten things you may not know about the Dust Bowl. Take the time to read the article for a quick overview of the effects of the black blizzards.

Some 850 million tons of topsoil blew away in 1935 alone. "Unless something is done," a government report predicted, "the western plains will be as arid as the Arabian desert." The government's response included deploying Civilian Conservation Corps workers to plant shelter belts; encouraging farmers to try new techniques like contour plowing to minimize erosion; establishing conservation districts; and using federal money in the Plains for everything from grasshopper and jack rabbit control to outright purchases of failed farms. This was the beginning of farm subsidies, something we live with today.

In 1944 just as it had thirty years earlier, a war in Europe and the return of a relatively wet weather cycle brought prosperity to the southern Plains. Wheat prices skyrocketed, and harvests were bountiful.

In the first five years of the 1940s land devoted to wheat expanded by nearly 3 million acres. The speculators and suitcase farmers returned. Parcels that had sold for $5 an acre during the Dust Bowl now commanded prices of fifty, sixty, sometimes a hundred dollars an acre. Even some of the most marginal lands were put back into production.

Then, in the early 1950s, the wet cycle ended and a two-year drought replaced it. The storms picked up once more. Bad as the "Filthy Fifties" were, the drought didn't last as long as the "Dirty Thirties." The damage to the land was mitigated by those farmers who continued using conservation techniques. And because nearly four million acres of land had been purchased by the government during the Dust Bowl and permanently restored as national grasslands, the soil didn't blow as much. At least a few lessons had been learned.

But now, instead of looking to the skies for rain, many farmers began looking beneath the soil, where they believed a more reliable — and irresistible — supply of water could be found: the vast Ogallala Aquifer, a huge underground reservoir stretching from Nebraska to north Texas, filled with water that had seeped down for centuries after the last Ice Age. With new technology and cheap power from recent natural gas discoveries in the southern Plains, farmers could pump the ancient water up, irrigate their land, and grow other crops like feed corn for cattle and pigs, which requires even more moisture than wheat.

The Ogallala Aquifer, whose total water storage is about equal to that of Lake Huron in the Midwest, is the single most important source of water in the High Plains region, providing nearly all the water for residential, industrial, and agricultural use. Because of widespread irrigation, farming accounts for 94 percent of the groundwater use. Irrigated agriculture forms the base of the regional economy. It supports nearly one-fifth of the wheat, corn, cotton, and cattle produced in the United States. Crops provide grains and hay for confined feeding of cattle and hogs and for dairies. The cattle feedlots support a large meatpacking industry. Without irrigation from the Ogallala Aquifer, there would be a much smaller regional population and far less economic activity.

The Ogallala Aquifer is being both depleted and polluted. Irrigation withdraws much groundwater, yet little of it is replaced by recharge. Since large-scale irrigation began in the 1940s, water levels have declined more than 100 feet in parts of Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. In the 1980s and 1990s, the rate of groundwater mining, or overdraft, lessened, but still averaged approximately 2.7 feet per year.

Increased efficiency in irrigation continues to slow the rate of water level decline. State governments and local water districts throughout the region have developed policies to promote groundwater conservation and slow or eliminate the expansion of irrigation. Generally, management has emphasized planned and orderly depletion, not sustainable yield. Depletion results in reduced irrigation in areas with limited saturated thickness and increased energy cost in all areas as the depth to water increases.

The future economy of the High Plains depends heavily on the Ogallala Aquifer, the main source of water for all uses. The Ogallala will continue to be the lifeblood of the region only if it is managed properly to limit both depletion and contamination. (For a video explanation of the Ogallala Aquifer click here)

Much has been said about the possible effects of the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline across the state of Nebraska and the potential threat to the Ogallala Aquifer. Today, nearly 25,000 miles of petroleum pipelines exist within the Ogallala Aquifer, including 2,000 miles in Nebraska. These pipelines transport about 730,000,000,000 barrels of crude oil across the aquifer — each year, including nearly 100,000,000 barrels of crude oil transported across the aquifer in Nebraska. After this oil is refined into gasoline, diesel fuel, aviation gas and other products, pipelines transport much of it back across the aquifer for use on Nebraska farms, ranches and roads.

The main pollutants to the aquifer come from the seepage of fertilizer and insecticides into the ground water system. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the state of Nebraska where corn production has skyrocketed due to the demand for corn for the production of ethanol. Corn is a very demanding crop on water and the use of fertilizer. Corn requires over 20 inches of rain per year and the average for the past ten years had been around 14 inches. This puts an increased demand on the ground water system.

Daniel Horowitz writes in his column “Obama’s EPA Continues Handouts for Rich Ethanol Farmers on the Backs of Consumers” in Red States:

“The single most regressive market-distorting policy to ever emanate from Washington is the absurd tendentious treatment of ethanol. Over the past decade, ethanol has been the poster child for the worst aspects of big-government crony capitalism. The ethanol industry has used the fist of government to mandate that fuel blenders use their product, to subsidize their production with refundable tax credits, and to impose tariffs on more efficient sugar-based ethanol from Brazil. These policies have distorted the market for corn to such a degree that 44% of all corn grown in the country is diverted towards motor fuel blends. If we would literally flush half the corn harvest down the toilet, we would be better off than using it to make our motor fuel less efficient.

Now, consumers are stuck with higher food and fuel prices, while rich farmers enjoy the favors of free legislation forcing people to buy their odious product. Although the subsidy has expired, the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS), which requires that 10% of all fuel be mixed with ethanol, is still in effect. There is no worse tyranny than using the power of the law to coerce citizens into purchasing an ineffectual product that costs more, and in turn, drives up the cost of everything else along the food chain.

Over the summer, the ethanol debate reached a new tipping point when the severe drought in the heartland destroyed much of the corn crop. At that point, even the obdurate knuckleheads in Washington began to wake up to the reality of the ethanol boondoggle. A bipartisan group of 156 representatives, 8 governors, and 25 senators petitioned the EPA to temporarily waive the ethanol mandate in the Renewable Fuels Standard until we recover from the drought. After dragging their feet for months, the EPA announced today that they have no intention on suspending the mandate for even one day.”

The benefits from ethanol are dubious are best. While being a boon for the corn farmers in Iowa and Nebraska the downside is great:

- The use of corn for ethanol drives up the prices and demand for corn,

- The refining of corn into ethanol takes more energy than the ethanol produces as a fuel,

- As corn is a mainstay in feeding livestock as the price of corn goes up so does the price of beef, pork, and poultry,

- Corn syrup (fructose) which is used in the production of soft drinks, juices, candy, energy bars, and many other items found on the grocery store shelves. And as corn increases in price so do those items.

In the PBS documentary a minor mention was made of the use of water and the depletion of the Ogallala. In this brief segment Ken Burns neglected to make any mention of the threat from the increased demand for corn and the potential hazards to the Ogallala. Was this due to Mr. Burns’ reluctance to take on a policy put in place by progressive government policies in the farm belt? He paid great heed to arousing the emotions and sympathies of the viewer to the actions of the federal government to alleviating the effects of the dust storms, but did not delve into the unintended consequences of the farm policies that grew during the latter part of the twentieth century.This is one of my problems with Ken Burns.

In driving across Nebraska on U.S. 30 (Lincoln Highway) for almost 300 miles

As a Constitutional Conservative I must admit I was very conflicted while watching the PSB Dust Bowl documentary. While viewing the film I had great empathy for the plight of the farmers and residents of the Dust Bowl, but I kept asking myself by what warrant did Congress and the Executive have in using taxpayer dollars to alleviate the effects of the black blizzards and instituting government policies directed from the White House. After research and contemplation I came to the conclusion that the actions taken by the government were in most part justified under the Constitution.

The first place I looked was the Preamble to the Constitution that stated:

“We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The words “insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare” were certainly applicable. We were on the verge of a revolution during the Depression and the domestic tranquility was at risk. Another phrase to consider is “provide for the common defense.” Our food supply was in trouble and a great portion of our rich topsoil was blowing away. This was a dangerous threat to our nation as an invasion by an armed enemy. The weapons of an armed invader would have been bombs, bullets, and bayonets while the enemy invading the Dust Bowl was drought, wind, and bad soil conservation. It was the obligation of the government, as George Washington said the first responsibility of the federal government was to protect the security of the nation.

The third phrase in the Preamble was “promote the general welfare”. While over the years this catch all phrase has been used by statist and Progressives to promote everything from welfare to birth control in this case it had a relative meaning.

The next place I looked was in Article I, Section 8.1 which states:

“The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;”

Once again our Founders gave weight to the power of Congress to collect taxes to support the common defense and promote the general welfare.

The final article in the Constitution that I looked at was Article IV, Section 3.2 that states:

“The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion; and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) against domestic violence.”

While this last reference may be somewhat vague I do believe that during the Great Depression, the dust storms on the Great Plains, and the great migrations there was a definite threat of domestic violence in the nation as people were losing their homes and land and our food production was at risk.

While there was controversy over having the Civilian Conservation Corps plant 100,000 trees as wind breaks and the Works Projects Administration employing Dust Bowl residents to build roads, irrigation, and sanitation projects I believe this was as necessary as our building defenses after the Japanese attacked us Pearl Harbor and German U-Boat sinking our merchant ships in New York Harbor and the Gulf of Mexico. The nation was at great risk and it was prudent for the federal government to take action to preserve the Republic.

The problem I now have is the aftermath of the measures taken to alleviate and mitigate the damage done by the black blizzards of the 1930s. Many of the government agencies we have today are outgrowths of Roosevelt’s and Congress’ policies of those days. Once a government agency is created for a national emergency they do not go away — they grow and expand their power as noted above with the EPA. We now have a plethora of alphabet soup departments and agencies like EPA, FEMA, and the Department of Agriculture that act as corporatist entities in regulating everything from the toilets we can flush to the light bulbs we can use. In many cases these regulations are not only encroaching on our liberties, but bringing about unintended consequences.

To protect fish on the upper Missouri River dams built for flood control are being destroyed. To provide additives for fuel corn production is up causing rising food prices and an increased depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer. Increased farm subsidies have lined the pockets of the big agribusinesses like Archer Daniels Midland while driving the small farmer off the land. These are just a few examples how the federal government has grown in power from those Dirty Thirties.

We will always have threats from nature to our national security and economy. We will have floods, draughts, hurricanes, and oil spills that will damage the economy of the fishing industry in the gulf. While it is the proper role for the federal government to protect against and alleviate these threats from nature we must be vigilant against the growth of government and its intrusion on our liberties.